An introduction to The Egg and the Rock

The Egg and the Rock is a Substack that is slowly turning into a book. This is how the book begins...

Science says the first word on everything, and the last word on nothing.

–Victor Hugo

PREPARE FOR THE TRIP: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE EGG AND THE ROCK

This is a book about the universe. All of it. At all levels.

As you can imagine, it’s tricky to know where to start.

But – after carefully mentally reviewing all 5,025,000,000,000 days of its history so far – I think we have to start in Italy, on the morning of the 17th of February, 1600.

In Padua, just inland from Venice, Galileo is 36 years old, and building his first telescope. But we’re not actually concerned with Galileo this morning. Fuck Galileo. He’ll be fine. We’re concerned with Giordano Bruno, five hundred kilometres away, in Rome.

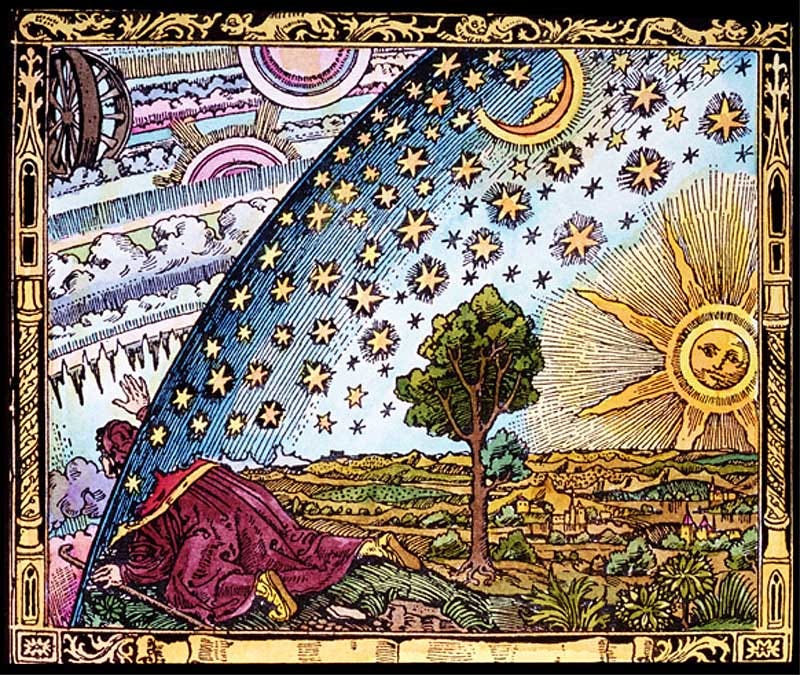

He has been on trial for seven years now, for, among other crimes, stating that stars are other suns, with other planets, where other living creatures no doubt dwell. Bear in mind, the first exoplanet – the first planet orbiting a star other than our sun – would not be observed for another 392 years. Now we know of thousands; pretty much every star we observe closely enough seems to have them. Bruno’s wild leap of imagination was correct. But it’s his wild imagination that has got him into trouble.

Had Bruno merely mathematically measured the distance to the stars, he would've been fine. But he had gone beyond the mathematics, gone beyond mere observation, and had foolishly extracted meaning from the data; he’d had a vision of what it all might mean. Unwise move. The Inquisition (or, to give it its full title, the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition) has finally, after seven years of confinement and multiple trials, found him guilty of heresy.

And now on this bright winter morning, the air crisp and cold, they slam an iron spike in through his right cheek, through his tongue, and out through his left cheek, ensuring he will not be able to transmit his heretical beliefs to the crowd. They then drive him on a mule to Rome’s central market square, the Campo de' Fiori (Field of Flowers), where they hang him upside down, naked, for a while, inviting the gathering crowd to jeer, before igniting the wood below him, and burning him alive.

They then ban all of his works. Those works will remain on the Index of Prohibited Books until the index is finally discontinued in 1966 by Pope Paul VI.

The Church will not apologise for his execution until the year 2000. (Exactly four hundred years after they murdered him; and eight years after the discovery of the first exoplanet).

Why I am starting my book on this day, the 17th of February, 1600?

Because, consumed in that fire, along with the body of Giordano Bruno, was the possibility of a certain kind of science.

A particular way of looking at the universe. A way which this book is, in some ways, attempting to revive.

THE GROWTH OF SCIENCE IN THE SHADOW OF THE CHURCH

Galileo finished building his telescope in 1609. He looked through it, at the universe. And he then faced the choice of how to describe what he saw. He knew there was, if you’ll pardon the term, a lot at stake.

And so he decided to describe it…

Mathematically.

He would not go beyond the data. He would not interpret the data. He would not extract the meaning from it. He would not deal with questions of meaning at all.

And so Galileo gave us only quantities, and deliberately left out qualities. In particular he, very deliberately, left out consciousness. Which means he left out pretty much everything that a human being can bring to the table – emotions; morality; spiritual and mystical insights; the peculiar, paradoxical, often painful truths of comedy; artistic visions – he left out all forms of knowledge which were not mathematical.

He left all those other realms of truth in the safe hands of the authoritarian religion that firmly controlled both art and philosophy. A religion which had an entire bureaucracy designed to find, try, and execute anyone whose truth did not match its revealed truth.

He left it to the murderers of Giordano Bruno.

Thus, when Galileo finally laid down the ground rules for modern science in 1623, he wrote:

The book of nature is written in the language of mathematics… The symbols are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without whose help it is impossible to comprehend a single word.

–Galileo Galilei, in The Assayer, 1623

And so Galileo tried to carve out a small, safe, new space in which to think in a certain specific, powerful, but limited way; and he, and his new way of describing reality – deliberately limited, purely mathematical, strictly quantitive – succeeded beyond his weirdest, wildest, most wonderful dreams.

Humanity has since then overpowered gravity itself, and left the surface of the earth to go into orbit, and even visit the moon, on mile-high pillars of flame. By 2021 (when the first private space agencies finally began to change things), 574 different people, from dozens of countries, had been in space. Superficially, they had been a varied bunch: men and women, straight and gay, of all colours and forty-one nationalities.

But look beneath the skin.

Galileo’s triumph has been complete. No priests went on those missions. No poets. No musicians. No visual artists. No philosophers. (And certainly no occultists.) Everybody, on every mission, from every country, for decade after decade, was a scientist or an engineer.

Every last one of them a child of Galileo, a fluent speaker of mathematics.

We had, essentially, sent the same brilliant, limited person, into space hundreds of times.

It hadn’t occurred to anyone designing, funding, or running these space programs that any other kind of person could be worth sending into space; could have an interesting new thought about the 99.999999% of the universe that isn’t Earth.

It hadn’t occurred to anyone that the response of a world-class comedian, or singer, or dancer, to zero gravity, might give us far more powerful insights into space, and humanity’s relationship to the universe, than seeing Scientist Five Hundred And Seventy Five write yet another report for the Journal of Aeronautics & Aerospace Engineering on how yet another type of crystal grows in zero gravity.

The problem, then, is that, in the west, in the 500 years since its humble, frightened birth, science has grown, vastly, in scale, power, and influence. Indeed, it has – with wonderful irony – taken over the role which religion once occupied, as the supreme arbiter of truth about reality.

THE FORGOTTEN VOW OF POVERTY

But the vow of poverty, the vow of humility, that science took at its birth – that it simply wasn’t qualified to speak about much of life, the universe, and everything – has been almost forgotten. Worse, flipped on its head: that whereof science cannot speak is no longer seen as the profoundly important stuff (too important for mere, self-limited, mathematical science), but as the frivolously unimportant stuff.

Science thus finds itself reflexively dismissing the truths expressed by the Buddha, Dostoevsky, Jung, Aretha Franklin… This leads to tremendous cognitive dissonance, inside and outside science; a dissonance which many scientists are aware of, but feel powerless to fix.

We are drowning in a sea of data and starving for knowledge.

–Sydney Brenner, while accepting the Nobel Prize for Biology, 2002

Contemporary science claims that it is humble; indeed, it genuinely believes that it is humble, that it embraces uncertainty, that it is always provisional; and yet, the way it plays out in the world is no longer at all humble, and is often deeply fearful of uncertainty.

If your claim is that the only valid road to truth passes through your very particular and narrowly defined form of humility... well, that's... not so humble.

And indeed many otherwise excellent scientists have genuinely come to believe that a rationalist materialist scientific approach to truth is the only valid approach to truth; and that the resulting edifice of scientific truths is the only valid edifice of truth.

That is, in some ways, completely understandable: the success of the scientific project at finding truth at ever more fundamental levels has been total: the standard model of particle physics, for instance, might be the most comprehensively successful theory of all time.

No wonder the physicist Sabine Hossenfelder can say (in her excellent book, Lost in Math)

As a physicist, I am often accused of reductionism, as if that were an optional position to hold. But this isn't philosophy – it's a property of nature, revealed by experiments.

–Sabine Hossenfelder

But it is hard to listen to Richard Dawkins (a wonderful scientist, and terrible philosopher), thunderously condemning the laity for not seeing that Genes Explain Everything At Every Level, and not hear some mediaeval pope or bishop tongue-lashing the faithful for the shallowness of their belief.

Hard not to read the famous last line of Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, on the consequences of finding a theory of everything (by which he means, in classic Galilean style, the smallest possible universe-explaining mathematical formula) – “…it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason—for then we would know the mind of God" – and not think that he is making a colossal category error.

Because, although the largely mathematical language of science gets better and better at explaining reality as you move down the scales, towards the fundamental particles, it gets worse and worse as you go up the scales – to blue whales, economies, or galaxies. It is therefore completely inadequate for describing the universe in its entirety, as a whole; and is inadequate in ways to which it is, by definition, utterly blind.

And that blindness is now having catastrophic consequences for our understanding of the universe, and our place in it: consequences to which it is, of course, oblivious.

And so, I want to describe the universe afresh, but I am trapped inside language that is almost perversely unsuited to the task.

LABELS

We are prepared to see, and we see easily, things for which our language and culture hand us ready-made labels. When those labels are lacking, even though the phenomena may be all around us, we may quite easily fail to see them at all.

–Douglas R. Hofstadter, author of Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid

The Egg And The Rock is an attempt to redescribe the universe. An attempt, that is, to put new labels on everything that is, and everything that has ever been, so that we can see more clearly how it all hangs together. As a result, I – and thus you, too – will continually trip over the stumbling block Hofstadter describes.

Because the universe already has labels on it. Down here on earth, there are often multiple labels for things: what you call a rabbit might be a bunny to my son Arlo; might be a beloved pet called Sandy to his friend Fahed; might be Oryctolagus cuniculus to a biology student. Might be a sacrifice to a fertility god in China. Might be a minor local god to an ancient Egyptian. Might be dinner to a hungry guy in Ireland. Might be a pest to a farmer in Australia. Different aspects of the rabbit – different aspects of the rabbit's relationship to the universe, and to other objects in the universe, and to us – are described by the different labels; all those aspects are available to you when you talk about a rabbit.

But once you leave earth and try to describe the other 99.99999999999999999% of the universe, you will find that there is currently only one set of labels; and all of those labels were put there by a very specific group of people – scientists. Indeed, by a very specific subgroup of those people – the astronomers, cosmologists, and astrophysicists.

And they speak the scared, defensive, purely mathematical language of Galileo. The language that won't get you burned at the stake, because it can say nothing about qualities; nothing about meaning. A language of great power, of course. No other language has so changed the world. But it is one which has become ever more specialised – ever more alienated from the other languages of truth.

When science now tries to speak of the universe as a whole, outside the realm of mathematics, it finds itself struck dumb: as though an iron spike had been driven through its right cheek, through its tongue, and out through the left cheek, making speech impossible.

Yet cosmology, astronomy, and astrophysics continue to speak compulsively, more and more so each year, in their ever more specialised dialects of scientific, mathematical language, about the disjointed parts of our universe.

It can be hard to get across to innocent civilians just how specialised these dialects now are. So let's just grab the titles of some recent papers in those fields. Bear in mind, these aren't cherry-picked, obscure sentences: these are the titles, designed to get across clearly the essence of the paper.

Evidence for the transition of a Jacobi ellipsoid into a Maclaurin spheroid in gamma-ray bursts

Insight-HXMT dedicated 33-day observation of SGR J1935+2154 I. Burst Catalog

OK, that's probably enough.

This kind of language can handle quantities superbly; but it cannot handle qualities at all.

Which is to say, it can deliver very precise data in almost unlimited quantities, but it cannot extract meaning from it.

This is the darker half of Galileo's great legacy. (And if you want to go deeper into that legacy, the philosopher Philip Goff explores it very fully in his book, Galileo's Error.)

But science was not always so tightly defined.

Earlier versions of science, like that of Pythagoras, wove mathematics into art, music, and religion: mingled quantities with qualities. (Indeed, Pythagoreanism was an entire, integrated, and delightfully mad way of life, mingling a philosophical school with a marvellously musical religious brotherhood.)

There is geometry in the humming of the string.

― Pythagoras

So there is going to be a tremendous linguistic tension in this book, between what I want to say, and the language available to me in which to say it.

If I stay inside strictly scientific language, I simply won't be able to describe what I see, because science, as it is currently set up, can't see it.

A PRECISE DEFINITION OF YOUR GRANDMOTHER

To understand the problem more clearly, imagine studying your grandmother the way we study the universe. (And bear in mind that your grandmother is simply a tiny subunit of the universe, generated by that universe and made of precisely the same stuff as galaxies, stars and planets: the thought experiment is entirely fair.)

You can use all the tools available to modern science – every telescope, microscope, spectroscope, viscometer, voltmeter, digital scales... but, having gathered your data, you must then describe her in purely scientific language; language acceptable to a peer-reviewed journal in one of the STEM fields.

You would have very little difficulty in communicating her mass, height, and position in space relative to the surface of the Earth.

Indeed you could probably articulate those aspects of her to a precision and accuracy seldom before applied to a grandmother.

But you would have extraordinary difficulty in articulating any of those aspects of her that matter.

Indeed, if you were studying her purely scientifically, in isolation, as an object, the very fact that she was a grandmother (a woman, a human, a mammal, an agent of her own destiny), would disappear, because all of those things are connections; they locate her in a deep, multilayered, evolved context, much of which exists entirely outside of the realm of STEM language.

There would be a number of papers on her hair (these would never mention toenails). More papers on her toenails (these would never mention hair). If one of those scientists were brave enough – were capable of looking beyond the boundaries of their narrow specialism – one of their papers might, daringly, note similarities in the rate of growth of her hair and the rate of growth of her toenails, and suggest a possible relationship.

They would, of course, be shot down for this. Indeed, it is unlikely such a paper would even make it through peer review: far too speculative, without evidence.

Where could they even publish such an interdisciplinary paper? The editors and outside reviewers at the various journals of toenail and claw studies wouldn't have the necessary knowledge of the field of hair studies to even evaluate the claims in the paper. Likewise, but in reverse, for the editors and external reviewers of the various journals of hair and fur research.

Meanwhile, under this intense observation, your grandmother, as an object of knowledge, would completely disintegrate.

And the more they studied her, the more detailed and specific the papers produced, the more she would disintegrate.

The higher they piled the data, the more invisible she would become.

That's what's happened to the universe.

TRAPPED TRUTHS

The world is full of things for which one's understanding, i.e., one's ability to predict what will happen in an experiment, is degraded by taking the system apart.

–R. B. Laughlin, in his Nobel Prize Lecture.

Laughlin (along with Horst L. Störmer and Daniel C. Tsui), won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1998 – and, like a startling number of Nobel Prize winners, he used the opportunity to urgently point out the limits of reductionism to his fellow scientists.

And yet, and yet, and yet… Having spent the past decade or more reading, with increasing fascination, scientific papers and books across multiple fields (Toenailology! Follicle studies!), I think they HAVE captured – in all this fractal, fractured, tortured data –astounding truths about the universe. They just haven't been able to recognise them; articulate them in a common language; and then connect them to make a picture of the whole.

They haven't been able to extract the meaning from the data.

They are not allowed: the secular religion that science has become won't let them, because it would involve thinking heretical thoughts. The kind of thoughts that led to the torture and murder of Giordano Bruno; to the murder of a broader, more fully human, science.

It is an almost cosmic tragedy, this trauma echoing through the centuries.

This problem of finding the meaningful information hiding inside the numbers, figures, images, and sounds of science, is far more profound than many scientists, and popularisers of science, realise. It is, among other things, a problem of language, which means it's a problem of thought. Science currently doesn't have the language to think the thoughts that are required to solve the problem.

Luckily, we have some clues as to how we might escape this trap. Because this has happened again and again throughout the history of science.

The great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, for instance, spent 25 years making the first accurate, detailed, day-by-day observations of the movements of the planets. He had an astonishing quantity of data – which contained everything he needed to make sense of the solar system – but he was utterly unable to extract the meaning from it. He died still believing that the sun, like the moon, orbited the Earth.

The much younger, and more daring, German astronomer, Johannes Kepler, finally extracted the meaning from Tycho Brah’s vast piles of data, and put the sun at the centre of the solar system; but it took Kepler many years to get there; to understand what he was seeing. Why? Because there was no concept, in the early 17th century, of a force acting proportionally to distance (as gravity does); and so there was no language for it. Without the language, he couldn't think the thought; the words did not yet exist.

How did he finally get there? By making analogy after analogy after analogy; approaching the truth crabwise, through metaphor, in a dreamlike process that looks nothing like how reductionist materialist science is supposed to look. He was, in the words of Arthur Koestler, a sleepwalker. (Koestler’s book, The Sleepwalkers, provides a superb account of Kepler’s agonizingly slow progress towards a new analogy, and thus new language, and thus new thought.)

This is the problem science always faces with new data containing new information: the new thoughts cannot be expressed in the old language.

NEW INFORMATION ABOUT INFORMATION!

Indeed, in a beautiful irony, information itself didn't have a language and a theory until Claude Shannon came up with one, in the 1940s. Before that, there was no easy way to talk about the larger patterns, rules, and laws that lay behind the many bewilderingly different forms information could take.

As the great popular science writer James Gleick said (in his book The Information),

The raw material lay all around, glistening and buzzing in the landscape of the early twentieth century, letters and messages, sounds and images, news and instructions, figures and facts, signals and signs: a hodgepodge of related species. They were on the move, by post or wire or electromagnetic wave. But no one word denoted all that stuff.

–James Gleick, from the prologue to The Information

Until you have a language suitable for expressing your theory, you cannot communicate your theory to others – or even formulate it clearly to yourself.

And cosmology’s tongue has been paralysed by an iron spike for so long, it can no longer even imagine a form of scientific speech that talks of qualities: of meaning.

After 500 long years, 500 circuits of the Sun, it has forgotten its tongue is paralysed; it thinks its purely mathematical speech is all that can meaningfully be uttered.

This is a tragedy.

Because there's a lot of meaning needs to be extracted: it's over 50 years since the pioneering astronomer Vera Rubin discovered that the movement of stars in spiral galaxies is nothing like the movement astronomy, and physics, had predicted. There are over a trillion spiral galaxies in our universe, and we cannot currently explain the movement of a single one. And no, the ever-changing amounts, and types, of entirely theoretical “dark matter”, “dark energy”, and, more recently, “dark fluid” hurled at the problem don’t count; they just throw the crisis into ever-higher relief.

They've had 50 years to solve this problem using a purely mathematical approach: in that time they have piled up more data than existed on Earth at the start of their search. (There is, for example, currently a radio telescope in Southern Australia – made from 36 individual dish antennas wired together – called ASKAP. That single telescope generates data at the rate of 100 trillion bits per second. That's more data, faster, than all of Australia's internet traffic added together.) And in that fifty years, gathering those unimaginable quantities of data, they've gotten, to use the technical term, absolutely fucking nowhere.

The language that makes sense of their data will clearly have to come from outside mathematical physics.

LOST IN A FOREST

To explain why – and to explain the approach of this book – let's return to Douglas Hofstadter, this time to his classic paper, Analogy as the Core of Cognition. He starts by saying that his paper

...shares with Richard Dawkins’s eye-opening book The Selfish Gene (Dawkins 1976) the quality of trying to make a scientific contribution mostly by suggesting to readers a shift of viewpoint — a new take on familiar phenomena. For Dawkins, the shift was to turn causality on its head, so that the old quip “a chicken is an egg’s way of making another egg” might be taken not as a joke but quite seriously. In my case, the shift is to suggest that every concept we have is essentially nothing but a tightly packaged bundle of analogies, and to suggest that all we do when we think is to move fluidly from concept to concept — in other words, to leap from one analogy-bundle to another — and to suggest, lastly, that such concept-to-concept leaps are themselves made via analogical connection, to boot.

–Douglas R. Hofstadter, Analogy as the Core of Cognition

Like Dawkins (and Hofstadter), I too am trying to make a scientific contribution mostly by suggesting to you a shift of viewpoint. As to how best to do that, I believe that Hofstadter is essentially correct. We think using analogies; but I'd like to subtly deepen and enrich Hofstadter’s own analogy. Hofstadter suggests that "every concept we have is essentially nothing but a tightly packaged bundle of analogies”, implying that all analogies are fungible; that any and all of them can potentially be bundled together with equal ease. I would suggest that it’s more complicated than that – that concepts are more like plants that come in a wide variety of types, and which thrive in certain cultural soils. Some analogies are delicate, some are hardy. Some cross-fertilise, graft, and hybridise easily, some do not. Some analogies are more easily uprooted and replanted than others.

And some cultural soils are more welcoming to new roots. The novel, for example, is a seedbed where almost any concept can put down roots and thrive: the soil of the modern scientific journal welcomes a far narrower range of plants.

Art should punch you in the brain, and you should stay punched.

–Marc Maron, host of the What The Fuck podcast, 2010

This book (and thus this Substack!) uses some of the techniques of art to unpack and make sense of the raw data of science. Art is a magnificently fertile jungle, a wild, uncontrolled space of perpetual hybridisation and cross-fertilisation; science, by contrast, has slowly become a series of neatly tended fields and forestry plantations, each one a monoculture.

The tragedy of modern cosmology and astrophysics, and of modern scientific language more generally, is its loss of the ability to use the full range of analogies (and thus thoughts) that should be open to it. Trapped inside the vast and wonderful grove of mathematics, and mistaking it for the entire forest – for the entire world – scientists are now punished for leaving that grove to explore other groves of analogy – many of them, also, vast and wonderful. Should a scientist bring back seeds from those other groves, and attempt to plant them in the grove of mathematics (to enrich the grove with new ideas from outside a narrow, reductionist, materialism), they are denounced as traitors to science, as pseudo-scientists, as heretics, and the seedlings dug up and hurled from the grove – seen, not as valuable plants bringing new properties to the grove, but as weeds.

Truths brought back from other groves are not even recognised as truths. The very soil, in the grove of mathematics, has grown hostile to new seeds; it no longer has the nutrients that seedlings need.

As a result, science, in confining itself to the grove of mathematics, is no longer able to think new thoughts.

So I have taken the liberty of doing some thinking for it.

As we travel together across this vast cognitive territory, I will try to generate a new, more useful, more revealing, more meaningful language, largely by analogy.

That is, I can’t write this book like a scientist, because writing like a scientist is what got us into this mess.

The crude real will not by itself yield truth.

–Robert Bresson, from ‘Notes On the Cinematograph’, translated by Jonathan Griffin

I am also going to quote many, many other writers as we travel: this book is a huge act of synthesis – not just a joining together of scientific papers and books across multiple unrelated fields, but a meshing of science with the other important human forms of thought and observation: art, philosophy, history, religion, each of which has powerful tools with which to observe the universe.

(And no you don’t have to believe in God to use the tools of religion, any more than you have to believe in Richard Dawkins to use the tools of science: it is simply a quirk of our cultural history that so much early, important human knowledge happened in places and times where the dominant language was religious – and thus became inaccessible to Galilean science.)

In quoting so liberally, I want to get across how many people have already glimpsed the picture of the universe I will be trying to paint here.

Their quotes will, I hope, provide a second, kaleidoscopic, lens through which to see the universe whole.

And so we are going to start very small, and work our way up. We are going to start with an egg. And a rock.

OK, that’s the introduction to the book. I hope you enjoyed it.

One last thing: I’m writing The Egg and the Rock in public, online, on Substack, because I want to create the audience for the book as I write it. You are a VITAL part of that process. Remember, you are not the passive reader of a finished book; you are the active reader of a work in progress. And I think this particular post is an excellent entry point for new readers; it’s the natural starting point. So I would like you to pause for a moment, before you leave this page and return to your life, and think; who do I know who would REALLY enjoy this? And then send them the link to this page. Actually do it.

It will also be more fun for you, if you have some friends reading alongside you. Like a high-tech, post-Gutenberg, work-in-progress book club.

Oh, and comments are of course very welcome below! Does this work for you as an opening? Is anything unclear? Do I belabour any points? How can I make it better?

But, once you’ve commented, please, do share this with anyone you think might be the book’s ideal reader.

And thanks for your attention! That was a long one…

Talk again soon,

–Julian

This is a fantastic introduction, and such an immense undertaking ! I'm going to have to read it a few more times i think :) Though i thought i'd share something because the passage where you wrote that no visual artists went to space (before 2021 that is) reminded me of Alexei Leonov - a russian cosmonaut, the first man to walk in space in 1965. He was artist first, and joined the military to support his family. He somehow found his way in the soviet space program and was the first person to make art in space - a view of the sun made with colorpencils. To think of the diffculty to bring *anything* in space, and the dangers of it at the time, and they still found a way to give him paper and pencils... He made a lot of paintings about his space travels, as well as a more "finished" rendition of the sketch he did in space (you can see it in this article https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/aug/31/first-picture-space-cosmonauts-science-museum-alexei-leonov and here an account of his first mission that absolutely gave me vertigo https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/the-nightmare-of-voskhod-2-8655378/ ) I know you were making a point about the hurtful split between art and science when it comes to the exploration of the universe, and the point stands ! But i cannot help but think of Alexei doodling in space, unaware he is the exception to the rule x)

I love your approach and the Grandmother Paradox is perfect :)

Like you, I’ve taken a wide interest in many facets of human activity.

Long ago, I concluded that science was largely based on the derivation of mathematical models of theoretical forms and their theoretical properties that together with certain theoretical constants and theoretical laws, determine their theoretical behaviour

We say a theory is valid when the theoretical behaviour of the theoretical forms maps or predicts the observed behaviour of observed forms. That is all.

No theory can ever get at the ‘essence’ of the forms, or of this Consciousness in which and to which the theories and the observations appear.

Nor can they say anything about the ‘lived experience’: the thrill and terror of battle, eating a meal with friends, arguing with the kids, listening to a sublime symphony or dancing to the beat of hard rock, noticing the foul stench of rotting garbage in a back alley... or any of the infinite experiences that arise within Awareness.

Good luck... I’ll be reading :)