Feedback Fun #1 (with lots of lovely links)

My feedback on your feedback on my introduction to the book.

Firstly, let me again welcome the thousands of new subscribers who have joined me over the past few weeks (ever since I posted I Wrote A Story For A Friend, and it went what I guess you'd have to call mildly viral).

The numbers have been quite overwhelming; I very much regret that I have not been able to greet you all personally, or answer all of your thoughtful comments, emails, tweets, DMs, replies-to-my-Welcome-email, etc, etc: at one point I was getting hundreds of messages an hour through all these channels. (They were arriving faster than I could read them, let alone respond.)

Anyway, as a result of all this excitement, almost 90% of you have now joined me in the past month. That essentially means that The Egg and the Rock has a brand-new audience, and is in some ways beginning again. So I must apologise to those hardy pioneers, the 10% who followed The Egg and the Rock back in the Dark Ages – a month ago! – before I Wrote A Story For A Friend: I will have to repeat myself a little for the benefit of the 90%.

As you probably know, if you've read my Welcome email, this particular Substack is an experiment: I am writing my next book online, in public, here. There are several reasons for this. Let us number them, and thus create the pleasant illusion that I am being rigorous and scientific!

A RIGOROUSLY SCIENTIFIC LIST OF REASONS WHY I AM DOING THIS, WITH NUMBERS AND EVERYTHING

1.) I love exploring new art forms, and I think Substack is potentially an exciting new artform. It’s subtly different from a standard blog, subtly different from a standard email newsletter. So far, it seems to be insulated from most of the problems you find on social media, and from the somewhat different problems you find on the open internet.

To use the metaphor I explored in my last post, right now Substack is a fertile seedbed where all kinds of ideas from all over the place can mingle, tangle, cross-pollinate, and flourish, without pests immediately arriving to destroy the crop. As a result, most of the writing I enjoy these days seems to be coming from Substack. Something interesting is happening here.

2.) I’m also writing here, in the open, for free, to spread the ideas in the book more widely, because I am excited by these ideas and think they deserve to spread. (It is clear, I hope, from the fact that I’ve written ten of them, that I love books; but a 500 page book, written in secret over a period of many years, and eventually furtively published, a year or two after that, as a $25 hardback that’s only available in a few hundred shops, is a terrible way to distribute ideas in the digital age.)

3.) A related point: I write here to find, and build, an audience for that future book as I write it – that is to find YOU: hi!

4.) And I’m also doing it in public to get feedback as I write, so that the ideas, and words with which I express them, have been thoroughly road-tested by the time the book comes out.

But, apart from all these sensible reasons, it's also

5.) …to show you the process of writing the book. To take you behind the scenes, and expose the whole mucky business of exploring an intellectual territory, with all its dead-ends and breakthroughs – because, in many ways, that’s a richer and more interesting experience than reading the finished, polished book itself.

But there is another reason for showing you the process…

6.) Because, when I started writing, as a teenager, I had no idea what a messy business bookwriting is – I just saw the finished, beautifully edited, highly polished books, and thought they were poured out like that in one brilliant go – and that view was both disheartening and completely wrong.

So I’m exposing the machinery a little here, in order that younger writers, and those who would like to become writers, can see the process in action, and have it demystified. So they can see how it is done, and how they could do it.

Oh! And there is a seventh reason!

7.) The original reason I set up this Substack, in early 2022, was because the theories I am exploring have far more predictive power than people realise, and I wanted to get my predictions up in public before the James Webb Space Telescope issued its first data. I did get my predictions up; detailed predictions on early galaxy formation; predictions about how common life will turn out to be in the universe; and a more general meta-prediction about how the flow of energy through the system will be found to organise the system, at all levels (universe, galaxies, stars, planets, lifeforms, cultures, technologies), no matter how far back you go.

And those predictions are turning out pretty well.

THE FEEDBACK

So, last week, I posted the introduction to the book, and asked for feedback. (If you didn't read it yet, please do! It's a good introduction to the whole project.) That was probably draft thirty, or something; don’t worry, I am not inflicting my first drafts on you. (My first drafts are almost unreadably rough – just a bunch of notes, thoughts, quotes, and questions that I’ll need to answer.) But no matter how many drafts a writer does, there will be problems that will not be uncovered until an audience reads it. And so it was!

Your feedback was great, and much appreciated. Overwhelmingly positive (hurray!) with some excellent specific criticisms (also hurray!).

KICKING GALILEO TOO HARD

Several people felt I had been unfair to Galileo. As Trisevgeni Papadakou put it, in a lovely email to me:

“I feel you are too harsh on Galileo, he did what he had to do to survive and pass on his legacy. We can't really judge him for wanting to stay alive.”

Yeah, I think that criticism is right: I had done that thing which writers often do (which human beings often do!): I had turned a complicated and nuanced tale, with no good guys or bad guys, into a simpler story of good guys and bad guys. If Bruno was the good guy, then Galileo (who navigated the Inquisition more carefully, and died in his bed age 77) had to be the bad guy. But of course, he wasn't anything of the sort: he was an incredibly brave man, who pushed the truth as far as it could be pushed. I mean, he died under house arrest, having been found guilty of heresy. His works were banned. So I'll rewrite that section to be fairer to Galileo. Thanks for the feedback.

Several people felt I was too hard on the scientific method more generally. DH put it very well:

"Yes, science has its own specialized language which is not amenable to expressing certain aspects of human experience. So what? Music also has its own specialized language (one that is largely opaque to me, not being musical myself). Other domains have their specialized approaches and terminology as well.

(…)

Science has other problems as well, such as politicization, the reproducibility crisis, and neglect of Feynman's dictum to be honest about the evidence both for and against one's pet theory. But I don't think there's anything intrinsically wrong with the language of science or the scientific method."

–DH

Yes, articulating what I am trying to say in this area is hard, and I may not have the balance right yet. The problem isn’t with the language of science per se, and it’s definitely not with the scientific method per se. It’s with the increasing tendency to treat them as the only valid language and the only valid method. But yes, I probably need to make it clearer how much I appreciate the astonishing power of the scientific method, and the virtues of rigorous scientific language in saving us from mushy thinking; from fooling ourselves with our own biases. Instead, I tend to impatiently say, sure, yeah, fine, whatever, reductionist materialism is great, but… and then spend ten pages outlining all the things it can’t do. Not fair or balanced.

DH also felt my criticism of science was too broad.

“…I don't think you can extrapolate from problems with cosmology, string theory, and perhaps other disciplines that have stagnated lately to all of science. Biology in particular is thriving -- at least if you steer clear of the politically contentious branches. When young people interested in science ask me whether they should pursue physics, chemistry, or biology, I always say biology, because that's where the excitement is and where progress is being made. (Alas, I am not a biologist myself, so I'm not just talking my book here.)"

-DH

This criticism is again fair. I do tend to wave my arms about and talk about the problems with “science” when often I really mean the problems with certain aspects of certain branches of science. I should probably make it clearer that I am mostly talking about cosmology, and astrophysics.

So, in general, I should be more precise in my criticisms of science, and more generous in my praise. Particularly if I want to woo hardcore reductionist scientists over to these ideas. Again, the problem comes from my impulse to make this a good guy/bad guy story (because I am used to writing novels! Because that is more exciting! Give me more conflict! More drama!) But nobody wants to be demonised as the bad guy. Useful feedback, thanks.

HOW TO SET FIRE TO PEOPLE YOU DON’T LIKE, BUT IN A NICE WAY

Lynn Watson wondered if Bruno had in fact been burned to death, or died a quicker and (one hopes) less painful death through smoke inhalation, before the flames reached him. This is a great question, because there were indeed different ways of burning heretics back then, some of which were more merciful than others. (“Mercy” is a strange axis along which to find yourself judging the killing of a human being by fire, but there you go; those were different times.) Sadly, it sounds as though, from the evidence we have, that the Roman Inquisition used a pretty painful method on Bruno.

But if anyone is interested in the various ways in which heretics were burned at the stake across Europe, this gives a fascinating short overview! It’s a little UK-centric (understandably, as it is part of the Capital Punishment UK website), but does also briefly cover the various methods used in Germany and the Nordic countries, by the Spanish Inquisition, etc.

(I am perhaps unusually interested in this area because I used to sing in a band called Toasted Heretic.)

MONKEYS, DOGS, AND ARTISTS IN SPACE

My assertion that governments had never sent an artist into space received some useful feedback too. It doesn’t change the overall picture all that much, but it does complicate it nicely around the edges.

hms_qutie informed me that the Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov was originally an artist, and did the first drawing in space: I had not known this!

"He was an artist first, and joined the military to support his family. He somehow found his way into the Soviet space program and was the first person to make art in space - a view of the sun made with color pencils. To think of the difficulty to bring *anything* in space, and the dangers of it at the time, and they still found a way to give him paper and pencils... He made a lot of paintings about his space travels, as well as a more "finished" rendition of the sketch he did in space – you can see it in this article, and here is an account of his first mission that absolutely gave me vertigo. I know you were making a point about the hurtful split between art and science when it comes to the exploration of the universe, and the point stands! But I cannot help but think of Alexei doodling in space, unaware he is the exception to the rule x)"

–hms_qutie

Good stuff. I particularly urge you to read the article hms_qutie links to, about Leonov’s first mission! I don’t want to spoiler it, but everything goes wrong, and it is a THRILLING read; more thrilling than most thrillers.

Teaser:

“I had to find another way of getting back inside quickly, and the only way I could see to do this was pulling myself into the airlock gradually, head first. Even to do this, I would carefully have to bleed off some of the high-pressure oxygen in my suit, via a valve in its lining. I knew I might be risking oxygen starvation, but I had no choice. If I did not reenter the craft, within the next 40 minutes my life support would be spent anyway.”

–Alexei Leonov, from this splendid piece in the Smithsonian Magazine

And Ezz pointed out that the US astronaut Alan Bean took up painting full time, after his retirement from NASA.

"Hi! Usually I don't comment on things, but this reminded me of an article I read a while back about an astronaut artist who did paintings about space when he returned. Couldn't find the article again, so I'm just linking to the wikipedia page here, and another site that shows his paintings. The article explained the stories behind two of his paintings, The Fantasy and The Fabulous Photo We Never Took."

–Ezz

I love this story, because if anything it reinforces my point that space demands an artistic response, as well as a scientific one. The experience of space turned Alan Bean into an artist: he simply couldn’t express his feelings fully through a mere scientific report.

Here’s a great quote from Bean – it’s from a Washington Post interview, back in 2009, when he was 77:

“I only think of the moon relative to paintings now. I wasn't an artist to begin with. Art was my hobby, and I was really an astronaut, a pilot. And as the years pass, I'm not that anymore. Buzz Aldrin will call me up sometimes, wanting to talk about space stuff, 'cause he's really into space stuff. And I say, "Quit talkin' to me, Buzz. I don't wanna think about it. I don't know anything about it. I don't wanna think about ways to go to Mars -- I'm not an astronaut anymore. I don't phone you to ask you what colors to paint these things. I love you, Buzz, but I am not gonna think about that anymore."

I'm a full-time artist.”

–Alan Bean

Michael Haines mentioned that Captain Kirk finally went where many men and a few women had gone before:

"And more recently actor William Shatner went into space and came back a changed man having seen the Earth as a tiny island upon which the whole of human history has played out floating in the immense darkness of space."

–Michael Haines

Yes, William Shatner was the main reason why, in my piece, I mentioned that things only started to change in 2021, when the first private space companies began sending people into space. I may mention him explicitly though, so people don’t trip over that.

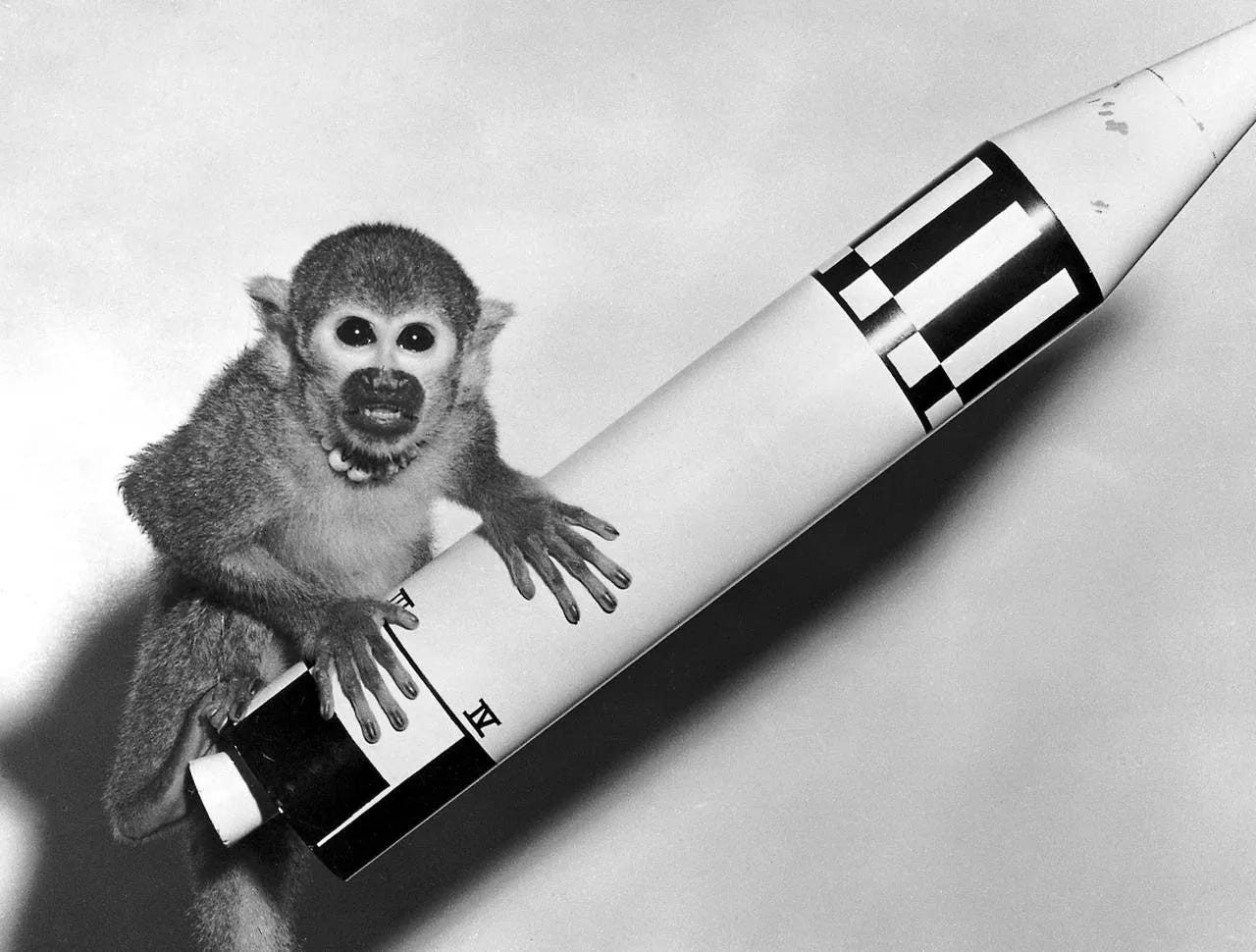

Finally, Lynn Watson pointed out that animals other than humans have been in space. True! I left them out because I was concentrating on the human side of space flight, but in fact the history of animals in space is far longer and richer than most of us realise. Fruit flies were blasted above the atmosphere and into the lower reaches of space in the nose cone of a captured Nazi V2 missile by the Americans as early as 1947, in New Mexico. A monkey, the first mammal in space, followed in another V2 in 1949. (It didn’t end well.) A pair of tortoises circled the moon in 1968, before humans did. Dogs, cats, mice, rats, rabbits, fish, frogs, tortoises, spiders, monkeys, apes, quail eggs, and LOADS of insects have all left the earth by rocket…

Well worth reading the Wikipedia entry on Animals in Space for a sprawling overview.

All in all, very fruitful feedback. It should make the introduction stronger. Thank you. Oh, and if you have further feedback, or anything else occurs to you, just put it in the comments, below.

THANKS, YOU’VE CHANGED MY LIFE

One last, non-scientific, piece of feedback: some people have said they don’t have fifty euro/quid/bucks to become a patron of this project, but they would like to be able to buy me a coffee. Well, that is very kind of you! You can do that through this Paypal link here.

And thanks again to all the people who have already made Paypal donations, and to all those who became paying supporters of The Egg and the Rock over the past month. It’s changed my life (I’ve even paid off my credit card debt! And bought a new woolly jumper!) – thanks to your gifts, I should be able to work on this Substack, and the book, for a significant chunk of this year, without having to do other writing stuff to pay the rent.

And to all of you, new and old subscribers, broke and rich, paying and non-paying alike; thank you for the gift of your thoughtful attention.

Have a great week. We’ll talk again soon.

-Julian

Julian, I’m writing a book took and may take your lead in opening it to scrutiny during the writing process. I also want it to be free.

One of the insights which you are free to use in your own writing is that science deals only in the behavior of forms. It tells nothing about ‘lived experience’: the thrill and terror of battle, the hug of a child, the stench of rotting garbage in a back alley, eating a pie at the footy, chatting with friends, a sublime symphony or the intoxicating beat of an African drums, or anything else that it means to be alive.

At its most rigorous science, uses mathematics to model theoretical forms (quantum field, sub-atomic particles, atoms, molecules, proteins, cells... all the way up to stars, galaxies, clusters and the background radiation) and their theoretical properties (mass, charge, spin, pressure, etc), that together with theoretical constants (Planck’s constant, the Speed of Light, etc) and natural laws (Conservation of Energy, etc) determine their theoretical behavior.

We say a theory is valid when the theoretical behavior of the theoretical forms reliably maps or predicts (not necessarily perfectly) the observed behavior of observed forms. That is all

Science can never say anything about the ‘essence’ of ‘things’ nor of this Consciousness in which and to which all things appear, including all theories and observed events and relations.

When scientists make observations they limit their analysis to the observed results, say apparent on a computer screen.

Yet, according to science, the screen is only apparent to the scientist as a result of invisible electromagnetic radiation emitted by the screen which is absorbed by the retina. At that point, there is neither ‘light’ nor ‘colour’ apparent.

Instead, the energy is transmuted into an electrochemical impulse that travels along the optic nerve (though nothing actually moves from one end of the nerve to the other; it is more like a line of falling dominoes). Only as the energy flow enters the visual cortex at the back of the brain do colors appear (no one knows how). The further mystery is that not only do the colors appear, awareness of the colours arises in the same process. It is as if ‘the observer and observed are one’.

On this analysis, there is no little person inside the head looking out through the eyes into the assumed material works. All that are ever apparent to any observer are the immaterial colors (and other immaterial sensations) that are one with the observer.

On this analysis, the existence of the ‘material world’ is a matter of belief that must be taken on faith.

Consciousness on the other hand requires no theory or belief.

It is ‘self-evident’

My book explores the implications of this Reality :)

I look forward to exploring the world and Consciousness with you

Hey, how can I not give a "like" to an article that quotes me! I appreciate the clarification of your position and which specific areas of science you're critiquing.

One point on reductionism. How common is this view among scientists really -- that is, outside hardcore particle theorists who arrogantly speak of a "theory of everything"?

I think there is widespread appreciation in science that there is a separation of levels. One can understand chemistry while knowing nothing of quarks. Even more so, knowing the internal structure of nucleons adds precisely nothing to one's understanding of chemistry. Similarly, while we do know that the laws of thermodynamics can be explained based on microscopic phenomena (the domain of statistical mechanics), they can also be understood and applied at a purely macroscopic level. And despite our knowledge that weird quantum behavior is happening all around us at the micro-scale, Newtonian mechanics is absolutely valid at the (sub-relativistic) macro-scale we experience.

Ask your favorite hardcore reductionist to derive the heritability of cystic fibrosis from the Standard Model of particle physics. If he handwaves that it's "in principle" possible but we just don't know all the details, tell him his belief is based on faith, not science.