The Blowtorch Theory: A New Model for Structure Formation in the Universe

How early, sustained, supermassive black hole jets carved out cosmic voids, shaped filaments, and generated magnetic fields

For scientists interested in citation, this post can be cited in Chicago style as follows:

Gough, Julian. “The Blowtorch Theory: A New Model for Structure Formation in the Universe.” The Egg and the Rock, March 19, 2025. https://theeggandtherock.com/p/the-blowtorch-theory-a-new-model.

DOI to follow.

THE PROBLEM

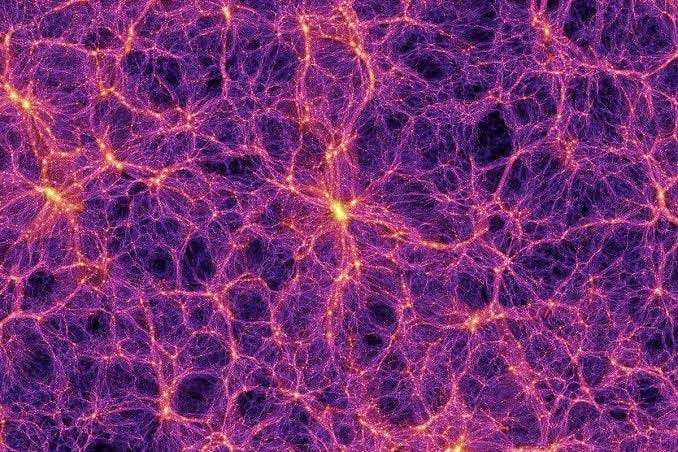

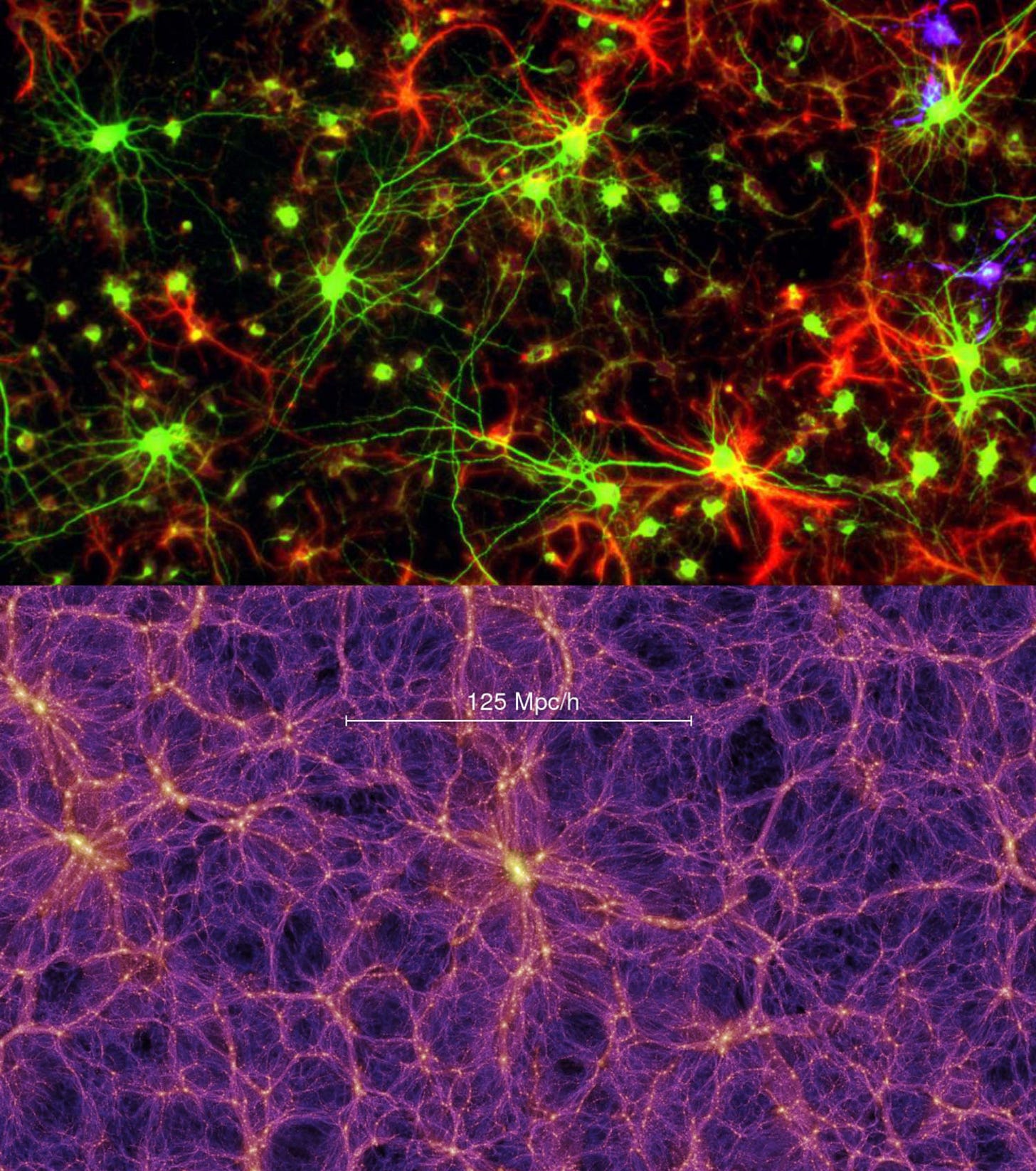

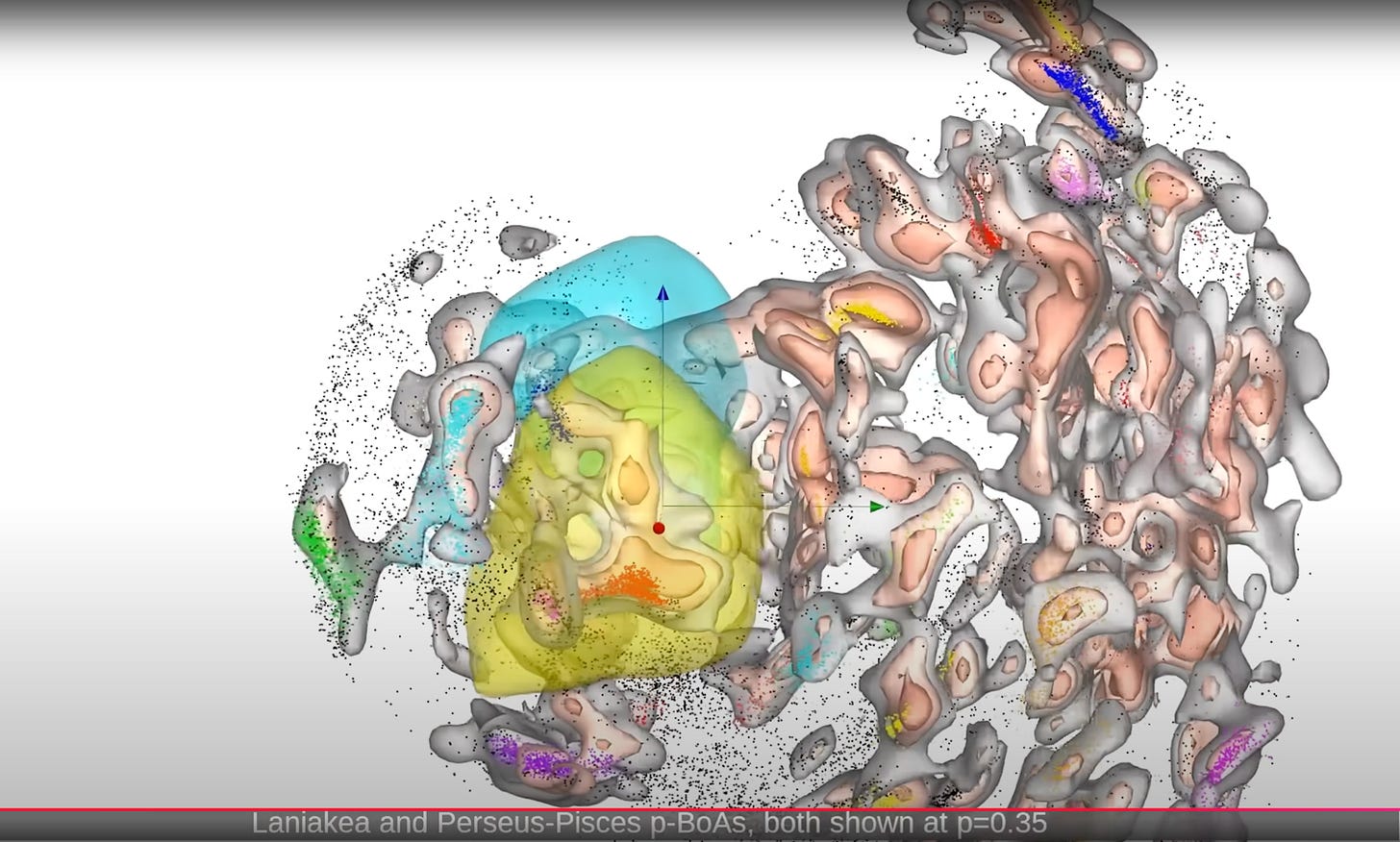

We have known since the 1970s that our universe has a complex structure. Dense nodes, packed with galaxies and gas, are connected by long, thin, filaments of galaxies and gas, all surrounded by largely empty voids. This structure resembles the neural network in a brain, and is known as the Cosmic Web. Its extraordinary scale and complexity was not predicted in advance of observation, and came as a huge surprise. So, how did all this unexpected structure form?

THE CURRENT, PASSIVE, ANSWER

The current mainstream answer to that question is called Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM ), and it is entirely passive. Based on gravity gradually pulling everything into shape, it requires huge quantities of (unfortunately, to date, entirely theoretical) “dark matter” to work. (Plus a lot of “dark energy” – that’s the lambda bit.) Despite decades of refinement, Lambda Cold Dark Matter still can’t coherently explain all the relevant observed phenomena without making some alarmingly ad hoc, post-observation adjustments. (See the Cusp/Core problem; See the Missing Satellites problem; etc.)

Crucially, it also predicts bottom-up structure formation, with mature galaxies assumed to form gradually, and hierarchically – that is, through a long, slow, random process of repeated gravitational mergers between much smaller, messier, and unstructured clumps of stars. This means it utterly failed to predict the rapid, early, efficient formation of huge numbers of large, bright, massive, startlingly mature galaxies revealed by NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope over the last two and a half years. Whether dark matter actually exists or not, it clearly isn't sufficient by itself to explain what we observe.

A new theory of structure formation is therefore required.

AN ALTERNATIVE, ACTIVE, ANSWER

In this post, I will lay out, for the first time in one place, a new, active, alternative model: the Blowtorch Theory of structure formation. It argues that large numbers of extremely early, sustained, supermassive black hole jets actively shaped the universe's structure in its first few hundred million years, largely through electromagnetic processes. These jets form vast, low-pressure cavities in the dense gas of the compact early universe, and lay down magnetic field lines, that – expanded by the universe’s growth, and shaped by later gravitational and kinetic events – go on to form the voids and filaments of the Cosmic Web we see today.

A MORE FRUGAL ANSWER

Importantly, this entire process of active structure formation by jets (assisted by gravity from ordinary matter) can be fully described without any need for dark matter. No new particles, and no new physics, are required.

SUPPORTIVE EVIDENCE

Recent evidence of unexpectedly large and early supermassive black holes (such as UHZ1 – which is as massive as all the stars in its galaxy put together), unexpectedly large and early jets (such as Porphyrion – which is a couple of hundred times longer than our Milky Way galaxy is wide, and indeed 40% longer than theory said was possible) – and, above all, large-scale extremely early rapid galaxy formation around active supermassive black holes, gives a great deal of support to this new theory.

(And even as this Blowtorch Theory post was being researched and written, a paper was published detailing an extraordinary blazar – a jet, a blowtorch, pointed straight at the earth from over 13 billion years ago, just 750 million years after the Big Bang – far earlier than Lambda Cold Dark Matter predicted, but slap-bang where the theory outlined here said we would find them. See: A blazar in the epoch of reionization, by Eduardo Bañados et al, Nature, December 17, 2024.)

The second half of this post will outline the parent theory – three stage cosmological natural selection – which successfully predicted these extremely early supermassive black holes, and their jets, plus the associated rapid early galaxy formation, in advance of the first James Webb Space Telescope data.

Blowtorch theory works, and can be explored, independently of its parent theory: however, three-stage cosmological natural selection gives an important and useful framework for more deeply understanding blowtorch theory and its implications.

But let’s start by laying out in more detail the problem our new theory solves.

INTO THE VOID

“And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.”

–Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil (1886)

THE PROBLEM, IN MORE DETAIL

Cosmic voids are vast regions in our universe containing almost no stars, galaxies, or gas.

They’re not vague, blurry, density fluctuations, either. These voids are sharply bounded, with densities about an order of magnitude lower than their surroundings. In the main body, density is less than 10% of the universe’s average (often much less); near the edge, it rises to 20%, and then sharply to 100% at the walls.

We didn’t predict their existence.

We only discovered them in 1978. (Hats off to Gregory and Thompson, and, independently, Jõeveer, Einasto and Tago.)

And we were startled to discover they take up more than 80% of the universe’s volume, while containing only a tiny fraction of its matter.

3D MAPS

In the late 1970s, large-scale redshift measurements of galaxies – tracking how far their visible light shifted into the red as they moved away from us – allowed us to map the universe with depth for the first time. Before this, our maps were essentially 2D, like a sheet of paper, with near and far objects overlapping; we had no way of knowing if a vast empty space separated them.

But with these new 3D maps, we discovered that over 90% of all stars, galaxies, and gas are crammed into just 20% of the universe. In fact, the majority of stars and galaxies by mass are packed into the dense regions we call clusters and superclusters, which occupy less than 1% of the universe’s volume. These clusters form dense nodes, connected by filaments along which gas appears to travel in massive flows.

The result is a dynamic network that resembles a brain’s neurons, or a city’s transport network, far more than it does random clouds of gas.

If you have trouble with cosmological visualisation (some don’t, some do), just imagine the universe as a country, and galaxies as buildings, ranging in size from huts to gigafactories: nearly all the buildings, especially the largest, are packed tightly together in isolated villages and towns (dense nodes containing clusters and superclusters), taking up only 1-2% of the land. An extensive network of roads, motorways, and canals (the filaments) connects these hubs, spreading over ten to twenty times as much land, mostly to transport gas for the star-making factories in the towns. The remaining 80% of land is almost empty. (Voids.)

These complex, network-like structures came as a huge shock to astronomers. 1981 was the year it became a crisis, when Robert Kirshner, Stephen Gregory, and Paul Schechter discovered the Boötes Void. It was 250,000,000 light years in diameter – so you could line up 2,500 copies of our own Milky Way galaxy, side by side, inside it. Such a vast space should contain thousands of galaxies – but the Boötes Void (now often known fondly as the Great Nothing) only contained roughly sixty…

This wasn’t just a failure of prediction; it was a revealing failure of observation. We had been looking at the entire universe – through a huge range of telescopes, across all frequencies, from radio to x-rays – for decades. Yet we had completely failed to see the actual structure of what we were observing.

This failure wasn’t entirely the fault of the astronomers; voids, after all, are empty, making them easy to overlook. But discovering the scale and sharpness of these voids threw into high relief a deeply revealing incorrect assumption that underlay all cosmology.

Astronomers had assumed, right up until this point, that our universe, on the larger scales, could be treated like a simple gas in equilibrium, with galaxies behaving like gas molecules, all spread out randomly. Sure, theorists like the great Belarusian physicist Yakov Zeldovich (father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb) had done some interesting work, in the early 1970s, on how matter might collapse asymmetrically under gravity – but prior to the redshift surveys of the late 1970s and early 80s, any astronomer or cosmologist would have told you that our universe couldn’t contain anything like the Böotes Void – let alone something like the Sloan Great Wall (discovered in 2003), a filament stuffed with galaxies and gas that’s 1.4 billion light-years long. From a distance, statistically, the universe was assumed to be entirely smooth, with no structure. Simple matter, obeying simple gas laws.

This incorrect assumption emerged from an even more fundamental unexamined assumption: that our universe was a one-off, with no history, in which randomly distributed matter with arbitrary characteristics blindly obeyed arbitrary laws, with random consequences.

That the first basic assumption had turned out to be utterly, eye-wateringly wrong should have led to some introspection in cosmology, astronomy, and astrophysics about the validity of the second, and even more fundamental, unexamined assumption. But it didn’t.

THE MAINSTREAM SOLUTION – LAMBDA COLD DARK MATTER – AND ITS FAILURE

Instead, they back-engineered a new theory from scratch, to fit the startling new data. Fair enough – when you’ve got something completely wrong, you need a new theory. But this “new” theory tried to fix the problem as simply as possible (since the deeper unexamined assumption was still that the development of our universe was just the simple addition of random processes), and thus relied on gravity alone. That might seem odd to you (and it should certainly seem odd to you after reading this post), given that electromagnetism is an astonishing 36 orders of magnitude stronger than gravity. That means the electromagnetic force exerted by a single electron is 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times stronger than the gravitational force it exerts. (Thus a modest fridge magnet, or some static from your hair, can cause an object to defy the gravitational pull of the entire Earth.) How can you leave electromagnetism out of the picture? But, in fact, this decision made total sense (given their unexamined foundational assumptions), and was entirely uncontroversial at the time.

That's because gravity is simple, and additive. Gravity can’t be blocked, reversed, or cancelled. Add more matter; it bends spacetime further; you get more gravity. That’s it, done. A large mass of matter will therefore always attract more matter gravitationally, and get bigger over time. But any large positive electromagnetic charge will attract nearby negative charges, which will immediately neutralise it. And so, in a random, chaotic, structureless environment, gravity is self-reinforcing: but electromagnetism is self-cancelling.

And so they understandably (but as we shall show, wrongly) assumed that electromagnetism couldn't have any effect at cosmic scales.

Zeldovich got back to work and, in papers like Giant Voids in the Universe (written with Einasto and Shandarin, 1982), and The Large Scale Structure of the Universe 1. General Properties. One- and Two- Dimensional Models (with Arnold and Shandarin, also 1982) found a way that gravitational collapse could give you something that approximated, roughly, to filaments and voids. Sure, the voids he got in these papers were too small, and too round (compared to what we were seeing), and there were a lot of other problems (it couldn’t really explain why galaxies were stable, and why everything didn’t just continue collapsing). But it was a promising approach, and we didn’t have any other theories. So, other cosmological theorists adopted it (Zeldovich himself died in 1987), and got to work developing it, adding an “adhesion model”, and a few other tweaks, to the original Zeldovich approximation, to try and make it work (i.e, get matter to stick together and actually produce galaxies).

There was one problem, however. When they added it all up, the matter they could see – the stars, galaxies and gas made from all the standard particles we know about, called for short “baryonic matter” – didn't have enough mass to pull everything into these extreme shapes by their gravity alone. But gravity was believed to be the only force capable of shaping anything at cosmic scales! This forced the theorists to introduce massive quantities of dark matter – imaginary particles that don’t exist in the standard model of particle physics, invented purely to patch up issues like this one (and so also the galactic rotation problem, certain gravitational lensing anomalies, some odd features of the Cosmic Microwave Background, etc.)

Since no one’s ever seen any dark matter, it can be given any properties you want. And that, regrettably but understandably, makes it extremely seductive.

Sprinkle enough of this marvellous stuff you’ve just invented precisely where you’d like it, give it the properties you most desire, and – what a wonderful surprise! – you can coax everything into the shapes we observe, using gravity alone. Kind of. If you squint. And if that doesn’t quite work, just add in Dark Energy (first proposed in 1998 - yeah, that’s the Lambda again). Or maybe Dark Flow (first proposed in 2008). Or Dark Radiation (first proposed in 2009). Or my personal favorite, Dark Fluid! (First proposed back in 2005). It has “negative mass” – yes, just like phlogiston (another imaginary substance that mainstream science once firmly believed in, for reasons which made a lot of sense at the time, but which turned out to be wrong). Whole Dark Sectors now exist: rich landscapes of imaginary quantum fields, across which wander escaped zoos of hypothetical particles, none of which have ever been observed. Dark photons! Sterile neutrinos! Axions! A new “dark” gauge group, why not, that is completely unconnected to the actual Standard Model gauge group! True, many of these later suggestions are fringe theories, with little support. But such new theories keep being proposed, because Lambda Cold Dark Matter, for all its undoubted successes (and you don’t get to be the leading mainstream theory without some big successes), keeps running into new problems, and therefore needs all the help it can get.

As you can see, with dark matter, like black tar heroin, once you’ve started, it’s hard to stop. And as time passes, you need more and more to get the same hit. After fifty years of tirelessly tweaking this wonderful, seductive, never-quite-there theory, how are we doing? Well, to drag everything into shape using only gravity now requires five times more dark matter than all the actual, observable, baryonic matter in our universe put together.

That’s the current mainstream explanation for filaments and voids. Five invisible universes worth of dark matter, with ever-changing properties that we never seem to be able to quite nail down, piled up on top of the one we can see. That – bizarrely – is considered the respectable, conservative theory.

Great. There's only one real problem: this respectable new theory is based on the same set of deep, foundational, flawed assumptions which led to the original embarrassing failure of prediction. The theory is, therefore, unfortunately, wrong.

PROBLEMS WITH ΛCDM

Does it approximate to the data? Sure, but so did Ptolemy’s earth-centred model of the universe (once you’d added enough epicycles). But there are, unfortunately, ongoing problems.

The Bullet Cluster was held up as evidence that dark matter is cold and collisionless. But the Trainwreck Cluster was held up, for a while, as evidence that dark matter is not cold, and not collisionless – that it’s warm, and self-interacting. (Warm dark matter has also been used to explain the cusp/core problem, etc.) If you keep changing the very fundamentals of what dark matter is, to suit each new, ambiguous, observation – if there is simply nothing solid there to hang onto – then you don’t have a theory.

Dark matter is basically a tiny, beautifully embroidered scientific duvet you can pull into position to cover any exposed area – but only at the price of exposing a different area.

For example, if you tweak your dark matter to suit big galaxies, it stops working for small galaxies. (The vexéd cusp/core problem.)

Meanwhile, adjust it to perfectly explain the numbers and sizes of the galaxies we see all around us today, and it massively overpredicts the number of extremely small dwarf galaxies in the early universe.

And the theory didn’t predict, and can’t explain, the recently discovered Ultra Diffuse Galaxies, DF2 and DF4 – which behave as if they contain no dark matter at all.

And now the new James Webb Space Telescope has finally shown us what's happening in the first billion years after the Big Bang… and Lambda Cold Dark Matter predicted none of it.

STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE, EVERYWHERE…

The early universe turns out to be rich in structure – including huge numbers of mature galaxies when the universe was just 4 or 5% of its current age, some containing supermassive black holes as massive as all the stars in their galaxy put together. (So, not the small, messy, random clusters of stars, and slow, bottom-up galaxy formation, that ΛCDM predicted.) But don’t worry, theorists are now busy “explaining” these, after the fact, by fiddling with their numerous free parameters (some models have up to ten) – essentially adding epicycles.

This doesn’t mean dark matter doesn’t exist (though I personally believe it does not, or certainly not in the form, and quantity, ΛCDM suggests) – but that, even if it does, it’s clearly grossly inadequate, on its own, to explain structure formation in our universe. With or without dark matter, there’s something else going on.

Back here on Earth, fifty years of increasingly expensive attempts to directly detect it have turned up nothing at all. (Except, of course, more funding for bigger versions of the same failed experiments.)

If the theory keeps failing at this scale, it might not be the universe that’s wrong, it might be the theory. Perhaps we've reached a point where we should stop trying to modify the universe with more and more imaginary matter, and start looking for a new theory.

The trouble is… It’s too late. For the past twenty years, the largest and most costly computer simulations of structure formation in our universe – running from the original Millennium, Millennium II, and Millennium XXL models, right up to the more recent Uchuu and AbacusSummit simulations – only include dark matter. Yeah, actual baryonic matter – the entire visible universe – is treated as a rounding error, and left out. Thousands of published papers are based on these simulations.

Are there some simulations that include baryonic matter as well? Recently, yes, sure – EAGLE, SIMBA, IllustrisTNG, Magneticum, Horizon-AGN, FLAMINGO – but they typically cover much smaller areas, with some just modelling the formation of a single galaxy. (FLAMINGO is the exception here, in trying to model large-scale stuff too.) This is in many ways understandable: the behaviour of baryonic matter (i.e. the real world) is absurdly complex compared to that of dark matter (which is a mathematician’s dream of simplicity – hi again, Zeldovich!). It’s therefore much harder to model, and far more costly to compute, which is another reason everybody left it out until computers got fast enough to handle it.

That’s not the real problem, though. The real problem is that none of these new simulations that incorporate baryonic matter simulate it from first principles: they simply adjust a whole bunch of feedback parameters that, in the real world, we do not know (black hole feedback, star formation rates, gas dynamics), until they get a result that resembles observations. Hey, if I tune all these dials enough, the result looks like a galaxy! Cool! Are the feedback parameters chosen accurate to reality? Er, nobody knows! They are just another bunch of tuneable parameters, piled on top of the six tuneable parameters for dark matter. This is extremely expensive CGI, not science. It makes ΛCDM completely unfalsifiable.

Or, as the great Von Neumann put it,

"With four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk."

–John von Neumann

Always reactive, never predictive: the dog of theory is simply chasing the car of observational data. The car turns left, the dog follows. Car turns right, dog follows. It’s a worrying sign, that the dog never knows where the car will go next.

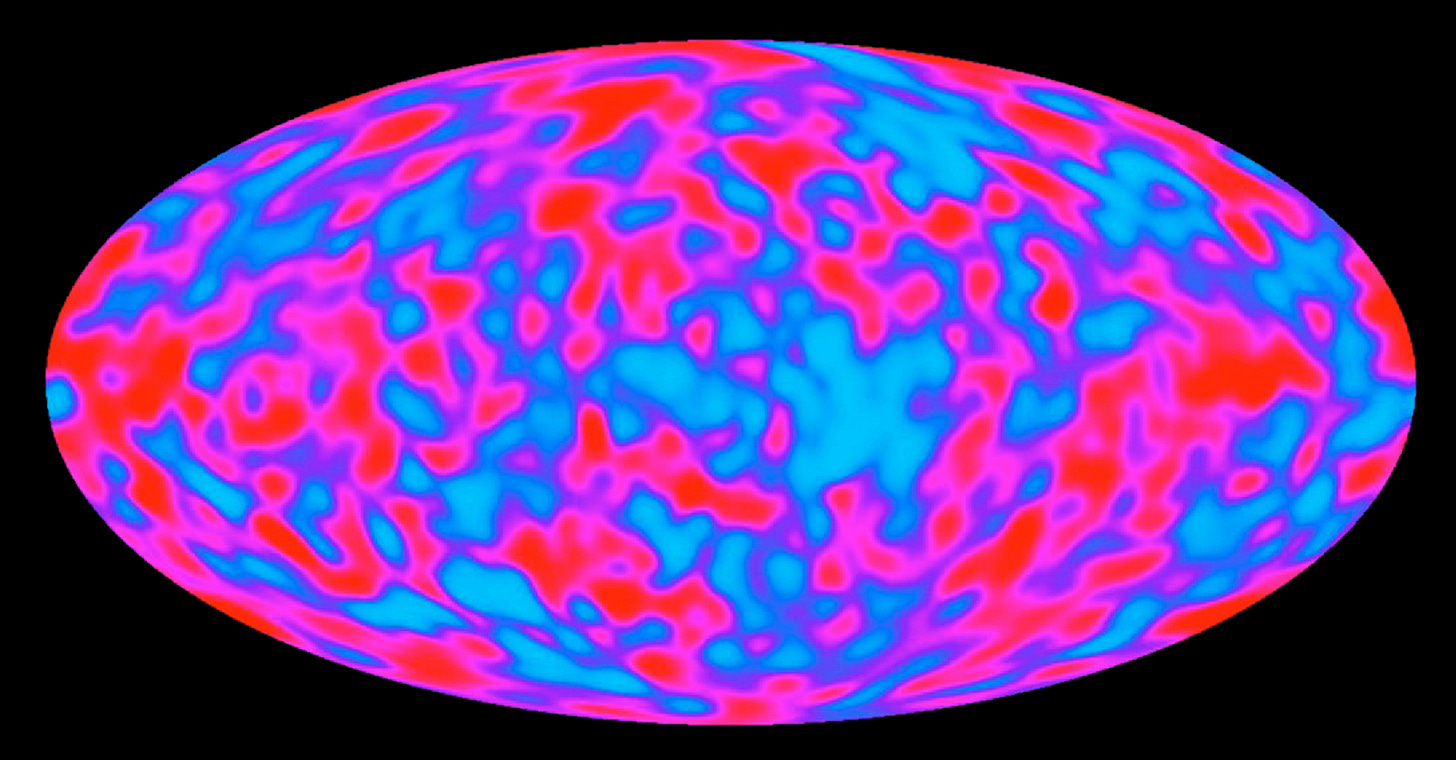

TWO CHEERS FOR COLD DARK MATTER

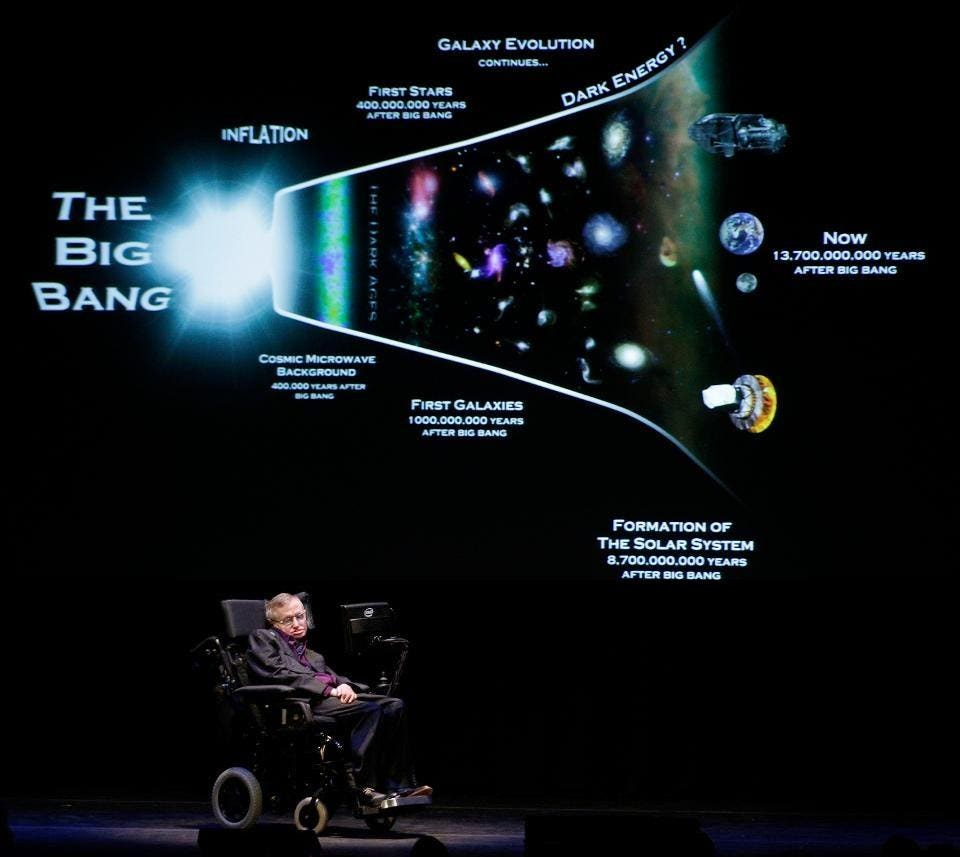

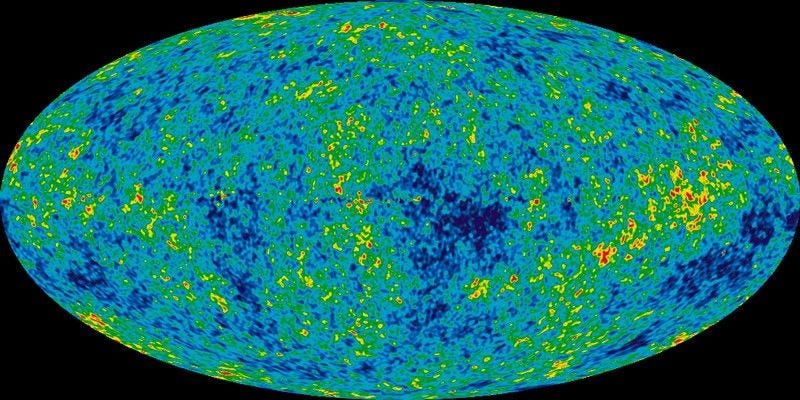

However, I don’t want to be too dismissive of Lambda Cold Dark Matter as a theory. No theory gets to dominate its field without some juicy, solid wins. Back in the early 2000s, Lambda Cold Dark Matter accurately predicted the Cosmic Microwave Background power spectrum – that is, it predicted the height of the soundwaves sloshing about in the tiny, ultra-hot, ultra-dense, fluid, early universe – in the brief era before light and matter uncoupled and released seventy percent of all the photons in the universe today in a single, universe-wide flash. (That flash, redshifted by the expansion of the universe, now forms the Cosmic Microwave Background.) NASA’s WMAP (the Wilson Microwave Anisotropy Probe), and the European Space Agency’s Planck space observatory, both confirmed waves of the specific heights predicted by ΛCDM – heights that didn’t make sense with just baryonic matter, but did with a lot of dark matter (and even more dark energy). That was a BIG win; after that, Cold Dark Matter became the “standard model” of cosmology.

MORE MATTER, OR LESS GRAVITY? (COKE, OR PEPSI?)

But if I’m going to mention that success, then I should also mention the successes of the main rival theory to ΛCDM, Modified Newtonian Gravity, or MOND. If ΛCDM tries to fix all the problems in the universe with more matter, then MOND tries to fix all the problems in the universe with less gravity. MOND’s also been around since the early 1980s, but, in 2021, it finally developed a model – the Aether-Scalar-Tensor framework, or AeST – which ALSO maps perfectly onto the acoustic peaks revealed by WMAP and Planck. (It does it by proposing a new vector field and scalar field that duplicate the effects of Cold Dark Matter in the early universe – see “Aether scalar tensor theory: Linear stability on Minkowski space”, by Constantinos Skordis and Tom Złośnik, and the more recent “Aether scalar tensor theory: Hamiltonian Formalism,” by Marianthi Bataki, Constantinos Skordis, and Tom Złośnik.)

So you can get a fit to the data with an imaginary, invisible new particle; but you can also get a fit to the data with an imaginary, invisible new field. I worry that the real truth we are uncovering here is that imaginary, invisible new things, with a bunch of free parameters, can always be made to fit the data.

ΛCDM and MOND are in fact now beautifully balanced in terms of success: ΛCDM is the most empirically successful for big-picture cosmology (except recently, as we have seen, in the early universe), while MOND is the most empirically successful on small, single-galaxy scales. And both are pretty bad at what the other is good at.

But MOND arrived at a full cosmological theory second, and so – despite being just as successful (and just as unsuccessful) as ΛCDM – must play Pepsi to ΛCDM’s Coke.

And Coke, as we have seen above, now dominates the world.

The fact that we have two theories with almost identical success and failure rates – yet one is built into every model, and the other completely marginalised – is a sign that what is going on here is sociology, rather than science.

But anyway, as a result of all this, dark matter is now baked into every mainstream model, as the single explanation for everything problematic, making it impossible to fix the actual underlying problems. They can’t even see what they’re looking at.

And so a lot of brilliant people remain trapped inside a faulty paradigm.

By contrast, the model I’m exploring actually predicts shit in advance.

Feel free to check: Predictions here.

…And in more technical form here…

…And more confirmation in accessible form here…

…And in more technical form here…

…And even more confirmation in accessible form here…

…And in more technical form here…

So, is there a theory that can explain voids, filaments, and their magnetic fields, using only the matter we can observe – the particles in the Standard Model of particle physics – and the established laws of nature?

Yes.

It’s called Blowtorch Theory. No, you haven’t heard of it, because this is the first time it's been laid out in full in public like this. (Yes, as some of you know, I’ve been working on it, behind the scenes – talking to scientists, researching, getting feedback – for months; building on ten years of earlier research for a book on cosmological natural selection. The specific, original inspiration for this post/paper, however, was this terrific paper in Nature, back in September 2024, by Martijn S. S. L. Oei, Martin J. Hardcastle, Roland Timmerman, et al, on extremely large, sustained jets: Black hole jets on the scale of the cosmic web.) But first, an uncharacteristically modest note, giving praise where it’s due…

WOBBLING HEROICALLY ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

Blowtorch theory ultimately emerges from cosmological natural selection (as I’ll explain later), and therefore grows from the American theoretical physicist Lee Smolin’s seminal ideas (which were in turn influenced by innovative work on evolutionary biology by the great Lynn Margulis and Stephen Jay Gould), as well as excellent later work by Clemént Vidal, John Smart, Louis Crane, Michael E. Price and others. Of course their work, like mine, owes a profound debt to earlier work on black holes by those titans of cosmology, John Wheeler, Kip Thorne, Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking, and to breakthroughs in magnetohydrodynamics by Steven Balbus and John Hawley (plus many others). I’m also borrowing from Priya Natarajan, Volker Bromm, Avi Loeb, and Marta Volonteri’s pioneering work on direct-collapse supermassive black holes. And of course, I’m building on the legacy of countless astronomers; far too many to list here individually. (Thank you, thank you, thank you!)

So, that was the background – both the science and the sociology, because both are important if you’re to fully understand the peculiar situation we are in.

Here’s the theory.

THE BLOWTORCH THEORY OF STRUCTURE FORMATION

I’m calling it the Blowtorch Theory, because new theories need a punchy name to break into the broader conversation. (But, if you’d be more comfortable with something respectably scientific-sounding, feel free to call it the Directed Plasma Overpressure Model, or the Localized Radiative Jet Confluence Hypothesis, or some other bullshit no one will remember.)

It starts with two observations.

The first: every one of the trillion or so galaxies in our universe that’s big enough or near enough for us to observe closely, appears to have a supermassive black hole at its center, with masses ranging from millions to billions of times that of our sun. And they have a power-law-like distribution: a few of the bigger ones, lots of the smaller ones.

The second: the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation – the light emitted by all that hot gas shortly after the Big Bang – is incredibly smooth. We know that the only density fluctuations in that gas are very subtle, less than 0.001%: we think they come from early quantum events, blown up vastly in size by inflation since the Big Bang. These density fluctuations occur at all scales, and have a power-law-like distribution: a few big ones, lots of smaller ones. Oh, and at the range of scales that would match the volumes of gas required to make the earliest, and therefore smallest, versions of all those supermassive black holes (they'll grow in size later), there are, to a very rough approximation – to within an order of magnitude – around a trillion of them.

Let's put those together.

Now, the smoothness of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation shows that the initial gas cloud in the early universe was much too smooth for easy star formation. (You need small, dense, pockets of gas in order to form stars.) This is a problem for the current, mainstream, bottom-up theories of star formation and galaxy formation, which start with the formation of scattered individual stars, somehow, from this smooth gas.

But this smoothness (with its occasional large-but-subtle, not small-and-extreme, density variations) is actually ideal for direct-collapse supermassive black hole formation. When the smooth gas cloud collapses across the entire large-but-subtle density fluctuation, there are no local, small, dense pockets that could otherwise break up into stars. It’s this smoothness which allows the entire vast field of gas to collapse directly into a single supermassive black hole.

And so blowtorch theory argues that all of these supermassive black holes must form now, inside the first hundred million years, and almost certainly within the first 50 million after the Big Bang. And they must form by direct collapse, semi-simultaneously, in a rapid, abrupt phase transition from what was, until then, an ultrasmooth cloud of gas.

AN OBJECTION CONSIDERED

A perfectly understandable mainstream objection would be that the fluctuations are far too subtle, too small – just 0.001%! – to trigger such a direct collapse of such a large area of gas. My argument, however, is that the conditions in the early universe are fine-tuned so that such fluctuations nonetheless do trigger such collapses, at a specific point in the expansion of the smooth gas.

I do understand mainstream resistance to this kind of argument-by-consequences, which can seem lacking in rigour. But please note that, similarly, in 1953, the British astronomer Fred Hoyle, using precisely this logic, predicted a highly unlikely resonance frequency in the carbon-12 atom, that would allow for the extremely efficient, complex (and unlikely) fusion mechanism of the triple-alpha process (where, deep inside a star, three helium-4 nuclei – alpha particles – are turned into carbon). He didn't predict this using mathematical logic: he predicted it because, when he looked around our universe, he saw a shit-ton of carbon everywhere, and it had to come from somewhere. Fusing three helium nuclei would do it, however unlikely that seemed. Hoyle had to urge his more cautious colleague, the nuclear astrophysicist William A. Fowler, to look for the necessary resonance. Grumbling, Fowler looked. And found it. (Amusingly, Fowler got a Nobel for this, in 1983; Fred, who had actually come up with the idea, didn’t, partly because he had annoyed too many people with some of his other, sillier ideas. Yes, I am aware that it’s a thin line between genius and just being spectacularly wrong! But walking that line is where all the fun is to be had…)

Similarly, in 1982, Dan Shechtman discovered quasicrystals with non-repeating, five-fold (or ten-fold) rotational symmetries were possible. This did not just require an unlikely level of fine-tuning: it was explicitly ruled out by the established laws of crystallography at the time. His paper was repeatedly rejected, the head of his lab told him to “go read the textbook,” then asked him to leave the research group for “bringing disgrace” on the team. When the paper was finally published, two years later, the most famous chemist in the world, Linus Pauling pissed all over him, saying, “There is no such thing as quasicrystals, only quasi-scientists.” But, when people finally actually looked, they discovered Shechtman was right. (He got an apologetic Nobel in 2011.) And the aperiodic, yet ordered, structures he discovered have novel mechanical, thermal, and photonic properties that classical crystals lack. Again, a highly unlikely level of fine-tuning that allowed for a complex outcome turned out to be true.

I predict it will, again, here, for reasons that will soon become clear.

PHASE TRANSITION

The ultrasmooth gas, expanding after the Big Bang, resembles a supersaturated cloud, which on a hot summer’s day can transition extremely rapidly from not-a-single-raindrop to a torrential shower, comprising millions of drops, all produced semi-simultaneously.

As the smoothness of the gas ensures nearly uniform conditions across the early universe, and as the subtle density variations are very thoroughly distributed across the universe, many regions should hit the critical threshold at the same time. In that phase transition, you should therefore see multiple, semi-simultaneous direct collapses – just like rain abruptly beginning in many spots within a saturated cloud.

It's likely that the shockwave from each of those initial direct collapses would compress nearby gas, pushing it past the collapse threshold, and thus setting off further collapses, in a cascading wave.

So you would see chain reactions in many localised regions, till they all meet – rather as, say, crystallisation spreads during the phase transition from water to ice.

WHY MUST ALL THE SUPERMASSIVE BLACK HOLES FORM EARLY?

The supermassive black holes all need to form together, now, at this early stage, from the smooth gas, because they won’t be able to later. Why? The gas will no longer be smooth enough – because these new, massive black holes are about to fuck up that smoooooooooth gas real good.

SWITCHING ON THE BLOWTORCH

Remember, each supermassive black hole starts with a mass of tens or hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, even hundreds of millions of suns, depending on the size of the fluctuation that triggered it. (The bigger ones are much less numerous. But they’ll all grow larger than this, later, as they eat more gas, and as some galaxies merge.) This intense concentration of mass begins to gravitationally attract enormous quantities of gas.

Why doesn't this gas orbit the black hole endlessly, and frictionlessly, like planets orbit stars? Because the shock of the collapse has ionized some of the surrounding gas, into positive protons and negative electrons. This ionized state makes it an electrically-charged plasma, generating electromagnetic fields and currents that cause turbulence. As the American astrophysicist Steven Balbus and his colleague John Hawley worked out in 1991, this turbulence acts as a remarkably efficient magnetic brake, transferring the plasma’s angular momentum outward, allowing the plasma itself to move rapidly inward, closer and hotter, forming a ferociously hot accretion disc – a blazing donut – locked tightly around the black hole. Some gas falls into the small mouth of the (dense, but tiny) black hole, bulking it up, but most of the gas just spirals closer for now, getting ludicrously hot from magnetic reconnection events (rather than mere particle-to-particle friction). Basically, a huge, hot, increasingly frantic queue builds up outside the exclusive, narrow, VIP entrance to the black hole.

“And the amazing thing is that even a very weak magnetic field would be enough to completely disrupt the stability properties of the gas. And that's what a lot of people had a hard time getting their head around.”

–Steven Balbus, co-discoverer of the magnetorotational instability. (Also known as the Balbus–Hawley instability.)

(Yes, yet another example of the Fred Hoyle / Dan Shechtman phenomenon. Evolved systems turn out to be extremely fine-tuned, at the level of the basic parameters of matter, so as to enable unlikely outcomes that lead to complex processes and structures…)

THE DYNAMOS POWER UP

Meanwhile, conservation of angular momentum means all the rotational energy of the initial vast, smooth cloud of gas is now concentrated into the much smaller black hole. (It’s supermassive, but it’s not big; millions of times the mass of our sun, all now crammed into a space far smaller than our solar system.)

This concentration forces the supermassive black hole to spin ridiculously rapidly, at close to its absolute maximum theoretical limit (so, pretty close to the speed of light), at the core of a hot, dense cloud of charged particles, the closest of which are now also spinning at nearly lightspeed. The whole system becomes a colossal dynamo, generating an absurdly powerful magnetic field from the rotating plasma.

This magnetic field now blasts two jets of hyper-energetic charged particles from the black hole’s poles: one north, one south. The dynamo electromagnetically accelerates these particles to almost light speed. (There goes all that shed angular momentum!) As they move this fast, you see relativistic effects – time dilates, particle masses increase relative to some guy watching from far away, all the fun stuff predicted by Einstein’s General Relativity. (Hence, “relativistic jets.”)

The jet is also collimated, meaning it stays coherent and narrow as it beams into the surrounding gas. They still can’t fully EXPLAIN how it remains so tightly collimated over such long distances; theory says Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities – turbulence, basically – should cause it to break up. But the further away in space they look (and thus the further back in time), the more the mainstream theory fails: Porphyrion, the 23-million-light-years-long jet described recently in Nature is, after all, 40% longer than theory said was possible. Yet again, fine-tuning means that highly unlikely orderly structure emerges from what a naive, everything-is-arbitrary, approach assumes should be random chaos. (Detect a theme?)

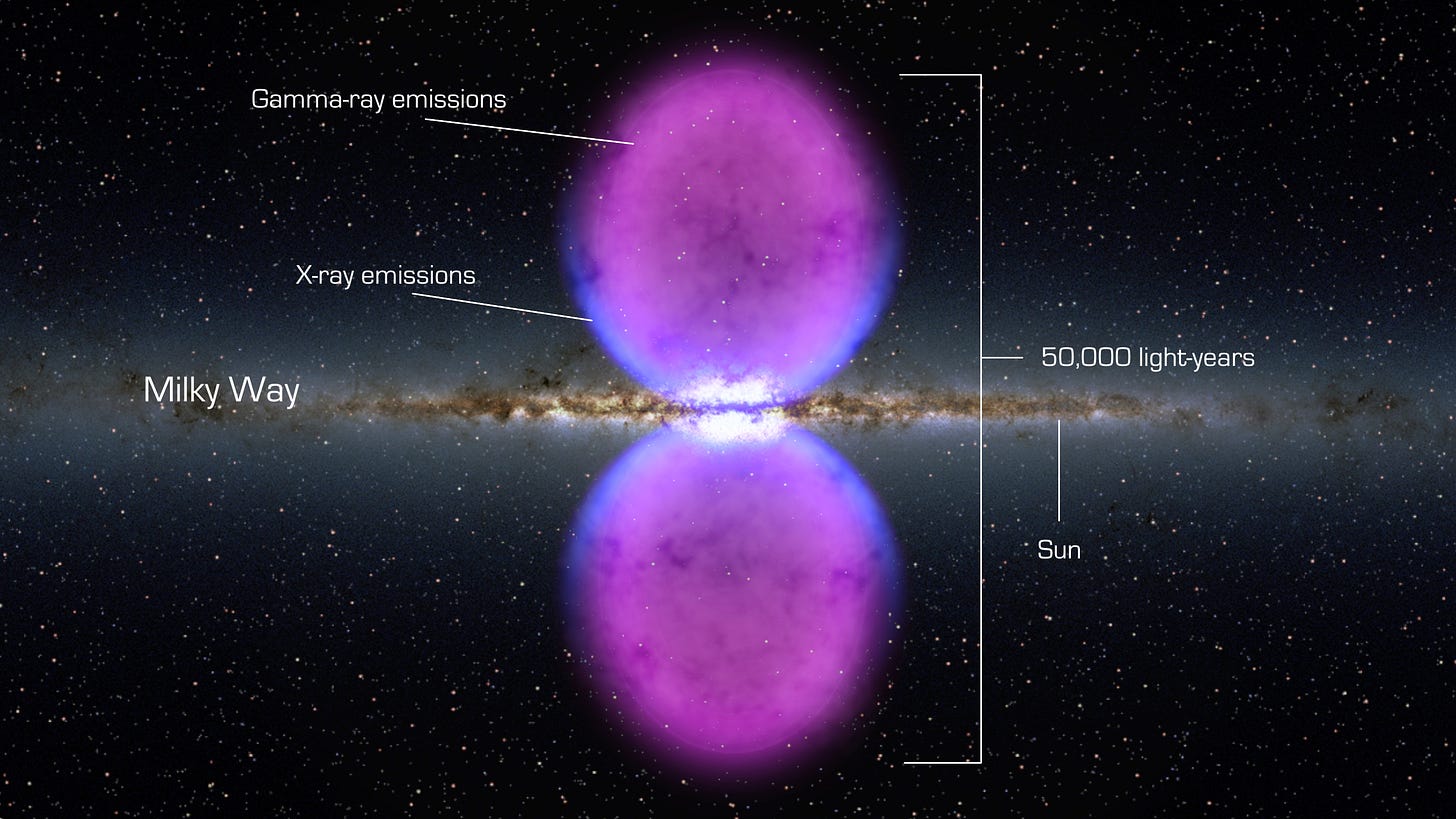

So, what does this tightly-focused, high-speed jet of charged particles do? A lot. It first sheds angular momentum from the hot gas “donut” around the black hole, stopping the donut from disintegrating and allowing more gas to fall in. But I’ll focus on the three most important later structural impacts of these jets: galaxy formation, void formation, and magnetic field formation (in galaxies, filaments, and voids).

1.) Galaxy Formation

Immediately surrounding the supermassive black hole is a hot, tight, fast-spinning donut of ionized gas. Further out lies a much larger, cooler, slower sphere of smooth gas, which has been drawn in by gravity. As it moves closer, this gas speeds up (thanks to conservation of angular momentum) and begins to flatten out into a much thinner, denser, disc. (Yeah, Zeldovich’s dear old pancake again.) The relativistic jet from the black hole blasts through this disc like a bullet through a water balloon, sending out pressure waves that disrupt the smoothness of the gas, causing pockets of density – and thus star formation. This cascade of star formation builds a tight, compact galaxy around the supermassive black hole.

I predicted this process in more detail two years ago, before the James Webb Space Telescope released its first data. (And I was right.) I won’t recap here, as I want to focus on the other two important structural consequences: void formation and magnetic fields.

2.) Void Formation

Many of these early relativistic jets just keep on going, reaching distances ten times, a hundred times, longer than the width of the galaxy forming at their base. And remember, I’m arguing that there's very roughly a trillion of these jets, in assorted sizes, nicely spaced out. As they streak through the pristine gas of the early universe at close to light speed, the jets generate massive shockwaves that push matter out of 80% of the universe.

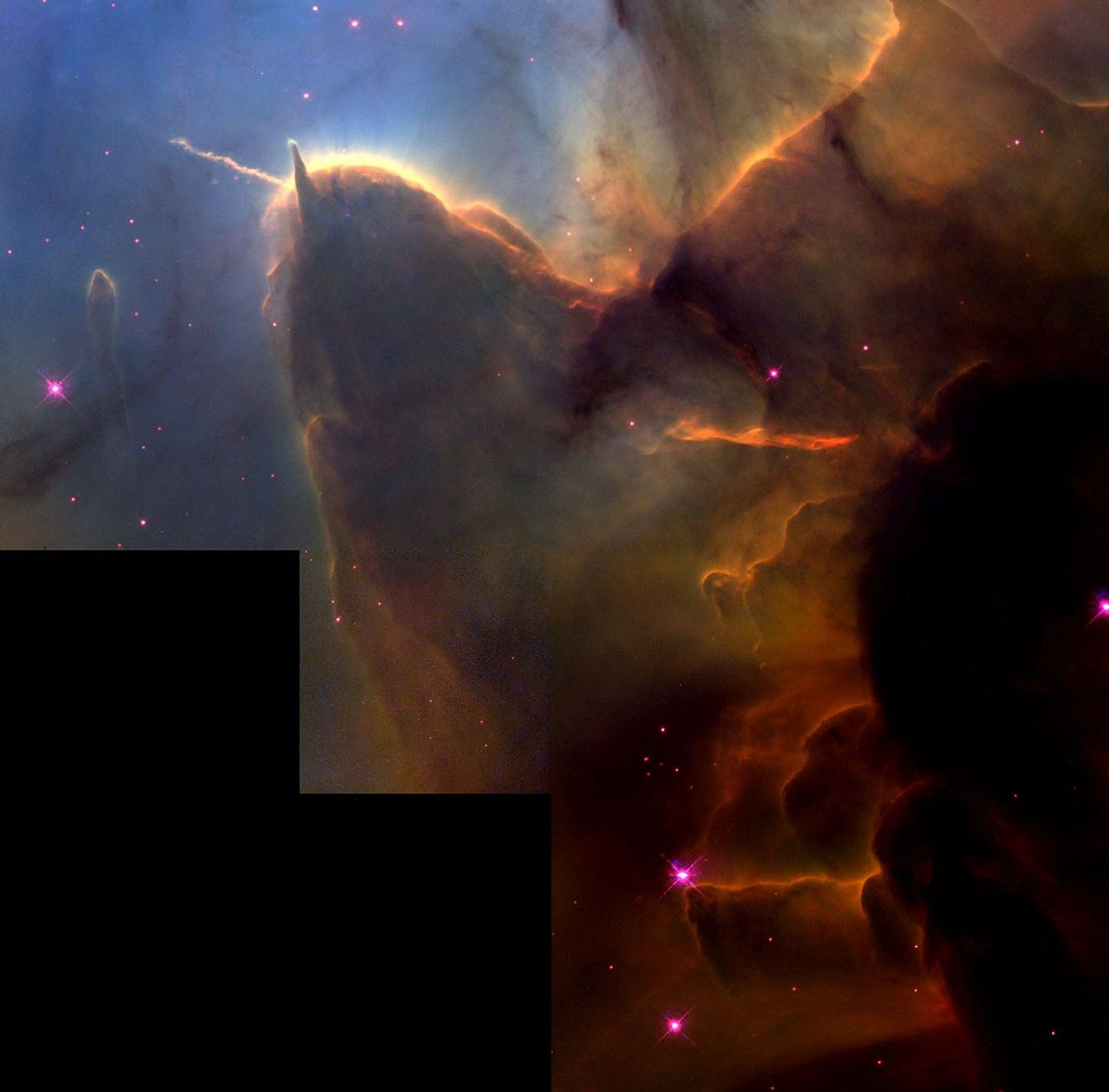

This is not fanciful. We know that, when fed gas, supermassive black holes fire jets from both magnetic poles. We know that, over time, these jets form huge, low-pressure cavities in the gas north and south of their galaxy. We see evidence of such lobes today – like the Fermi bubbles (which we only discovered in 2010), north and south of our own Milky Way galaxy, probably caused recently by a brief firing of jets from our galaxy’s own supermassive black hole (as some gas, or a star, fell in).

We know that older cavities tend to be larger, because they formed when gas in the vicinity of the supermassive black holes was denser and more plentiful, providing the fuel for longer, more powerful jets. (For example, a marvellous 2024 paper by Francesco Ubertosi, Simona Giacintucci, Tracy Clarke et al, on galaxy cluster Abell 496, shows cavities within cavities within cavities, with the oldest being the largest.)

My prediction here is that the dense gas of the early universe feeds sustained, powerful jets, which generate vast, early cavities that continue expanding, eventually detaching from their jet source (which eventually runs out of fuel, and switches off). These cavities, formed by an electromagnetic jet, will have (I’m arguing) a weak but effective electromagnetic boundary – rather like a soap bubble’s skin – so when they encounter other cavities, their electromagnetic skins could simply merge, forming larger voids. The universe’s expansion should then hugely expand them over time.

Blowtorch theory argues that is what generated today’s voids, with their blurry balloon-animal shapes.

A trillion dynamos, switching on a trillion blowtorches, early.

In pushing gas out of 80% of the universe, these jets are building dense gas reservoirs in the remaining 20%: the narrow spaces, or filaments, between voids. Reservoirs the galaxies will draw on later, using the third thing the electromagnetic jets are building. Something they are particularly suited to…

3.) Electromagnetic Fields! (and thus Filament Formation!)

The electromagnetic jets in this high-powered, early era – jets sometimes ten, fifty, even a hundred times longer than the galaxy at their base – are also laying down an electromagnetic circulatory system. This is important: Lay down magnetic field lines early enough, and you constrain the future development of the entire universe.

MAGNETIC FIELDS CONSTRAIN AND GUIDE IONISED GAS

Here’s why. Magnetic fields constrain and guide ionized gas (plasma). Within a magnetic field, plasma can’t move freely in all directions: it moves much more easily along magnetic field lines than across them. Processes like heat conduction, viscosity, and diffusion also become highly directional in a magnetic field. So, movement, heat distribution, energy flow – everything in a magnetic field follows the path of least resistance along those field lines.

In this way, magnetic fields act like tram tracks for charged particles (or arteries, if you’d prefer a 3D analogy), organizing the energy flow, and mass flow, that structures the system.

“Anytime astronomers figure out a new way of looking for magnetic fields in ever more remote regions of the cosmos, inexplicably, they find them.”

—Natalie Wolchover, Quanta Magazine, from The Hidden Magnetic Universe Begins to Come Into View, July 2020.

True, though I’d remove the word “inexplicably.”

EXPLAINING MAGNETIC FIELDS IN VOIDS

We recently discovered that even voids contain faint electromagnetic fields. Currently there is no generally accepted theory for how those fields got there. Blowtorch theory argues that they were left by the jets that sculpted the voids.

EXPLAINING MAGNETIC FIELDS IN FILAMENTS

The magnetic fields in the filaments connecting denser regions? Those are the electromagnetic ghosts of the original ultra-powerful, ultra-long jets. Basically, electromagnetic pipes. Their field lines link back to the centers of the galaxies that produced them, establishing a cosmic plumbing system that will, over time, drip-feed back to those galaxies the gas they previously pushed away into dense reservoirs.

EXPLAINING THE ABRUPTNESS OF THE DENSITY GRADIENTS

This also explains the abrupt tenfold change in density between filament and void. (Which is a major problem for Lambda Cold Dark Matter.) Without electromagnetic containment, gravity alone should, over time, simply blur out this abrupt density transition. Gravity drops off smoothly with distance, not abruptly, by an order of magnitude, at a specific point. Similarly, gas, even in open space, should slowly diffuse from high-pressure areas to low. Yet that, too, does not seem to be happening to the extent that a purely gravitational theory predicts. The maintenance of such hard boundaries over billions of years makes perfect sense, electromagnetically: it doesn't make any sense gravitationally (with or without dark matter).

However, I don’t want to give you the impression this whole process is ultra-efficient, with totally clearcut boundaries. The formation of galaxies, voids, and filaments is messy (as processes evolved through blind Darwinian evolution tend to be); galaxies crash into each other, some gas gets stranded, filaments combine, and tangle. It’s more like Darwin’s entangled bank than a smoothly operating machine.

But that’s fine, because, from evolution’s point of view (and I'll expand on this shortly), the important thing is to get the gas moving now, and to lay down magnetic field lines that can capture it and direct that movement. Galaxies are hurriedly laying cable, laying pipes, building reservoirs and filling them, while everything is still close together; while it is still easy. (Just as an embryo grows its arteries and veins while still in utero.)

Once in place, these magnetic field lines essentially “freeze” into the plasma. As the universe expands, the field lines thus stretch and expand along with the plasma itself (albeit weakening due to flux conservation).

SOPHISTICATED, POWERFUL, EARLY, ELECTROMAGNETIC STRUCTURE FORMATION

The key point: Early structure formation in our universe is primarily electromagnetic, not gravitational. Gravity does the grunt work of pulling (particularly pulling together the clusters and superclusters), but electromagnetism does the sophisticated work of shaping and directing.

And, note, this model needs only baryonic matter – the stuff we can see. No dark matter required. (You can leave it in the picture if you wish, but why? It isn’t necessary.)

There will be a couple of obvious questions, so let me answer them here.

Q: But the voids we see today are up to a hundred million light-years wide, or even larger! And the jets we see today are far smaller than that, peaking at a few million light-years in length! So how can such small jets make such large voids?

A: Because those voids were made early, when the universe was still extremely dense and compact. At redshift 20 – roughly 180 million years after the Big Bang – our universe was 20 times smaller in diameter than it is now, with gas therefore nearly 9,300 times denser. (The average density of matter in the universe scales as the cube of the inverse of the scale factor – or, less technically, if you shrink the universe in all three dimensions, you squeeze the living fuck out of the matter.)

By redshift 10 – or 500 million years after the Big Bang – the universe was still 10 times smaller, and gas was 1,300 times denser than today. So those early jets didn’t need to travel vast distances to have massive effects. Jets were pushing between a thousand and ten thousand times as much gas out of the way as they would over a similar distance today. And, over time, the universe’s expansion would make these early voids ten or twenty times longer, and wider, and taller – and thus thousands of times larger in volume – than they were at redshift 10 or 20… but they began relatively compact.

Moreover, there was much more, and much denser, gas in close proximity to supermassive black holes in the early universe. Enough available gas to feed their dynamos, and thus sustain long, powerful jets, over extended periods – tens or even hundreds of millions of years; far longer than what we see today in our vastly expanded, far more diffuse cosmos.

As in most evolved systems, key structures form remarkably early, while it’s still easy. A human embryo, for example, has decided which end will eventually be head, and which feet, by day five, when it’s a mere 64-cell blob, less than 0.2 millimetres in diameter. Likewise with our universe.

Q: But if the jets from the core of the new galaxy push gas out of the voids, why don't they also push gas out of the galaxy, switching off star formation?

A: Because this is a complex, evolved system doing a complex, evolved job. The same dynamo effect that drives gas away from the galaxy’s poles (perpendicular to its disk) is simultaneously, by removing angular momentum from the gas at its equator, allowing that gas to spiral rapidly inward, forming new stars and feeding the jet. Gravity, electromagnetic fields, and pressure gradients combine to create a vast cosmic pump, steadily drawing in fresh gas. This pump can operate continuously for tens or even hundreds of millions of years.

Currently, the mainstream theory is, indeed, that jets quench star formation by driving gas out of the galaxy. But that view came from observing mature, relatively nearby galaxies, many billions of years after the Big Bang, where these pumps are older, erratic, running out of fuel, and beginning to switch off, coinciding with the end of rapid star formation. Correlation; not causation. Meanwhile, pre-James Webb Space Telescope, we had no data on the early, high-power phase.

What I predicted back in 2022, and what the James Webb is starting to see strong evidence for, is that, early on, these jets do the opposite – they’re driving star formation, not quenching it.

Q: You say Blowtorch Theory shows we don't need dark matter. But isn't dark matter required to explain galactic rotation, and disc galaxy stability, and gravitational lensing, and the galactic dynamics of dwarf galaxies, and acoustic peaks in the Cosmic Microwave Background, and the Universal Rotation Curve, and…

A: Currently, yes, simply because every outstanding observational problem has dark matter thrown at it, as the only possible explanation. This is partly because dark matter is so fuzzily defined, with so many free parameters, you can massage it to “solve” almost any problem. (Why did your grandmother slowly but steadily move UP the stairs, in defiance of the laws of gravity? Because there was a large halo of dark matter at the top of the stairs, pulling her. See? Problem solved. No need, now, to look for a more complex, evolutionary, dynamic-systems explanation.)

I’m not arguing that blowtorch theory also solves all the other outstanding problems currently explained by dark matter. It doesn’t. I’m making a broader point: that an evolved-universe approach will generalise to solve the other outstanding anomalies. They may well all have quite different explanations. But, as with structure formation, the answers are likely to lie in the sophisticated behaviour of the things we can see, not the simplistic behaviour of a thing we can't. By the way, this makes Blowtorch Theory an excellent fit with David Wiltshire’s Timescape cosmology. (See his important recent paper, “Solution to the cosmological constant problem”.) Timescape deals with Dark Energy’s contribution to structure formation; Blowtorch Theory deals with Dark Matter’s contribution to structure formation. Indeed, it is quite likely that, as we find better, more sophisticated explanations for each of these different anomalies, dark matter will slowly fade away, without any big “eureka!” moment. (Or whatever the negative of “eureka!” is.)

DARK MATTER IS THE MODERN MIASMA

This is a classic example of the Single Variable Fallacy, or maybe better The One-Missing-Piece Illusion. A very human cognitive shortcut that assumes there must be a single missing factor that can explain all discrepancies. We made this mistake before, when we blamed all disease on “miasma” – also known as “bad air” and “night air”. “Miasma” almost-but-not-quite explained everything. (The Black Death! Cholera! Chlamydia! Malaria, whose name literally means bad air in Medieval Italian! Oh, and obesity was caused by inhaling the odor of food…)

“Miasma” was the dominant theory of disease, worldwide, for two thousand years, until the late 19th century. But the actual answer to “what causes disease?” involved bacteria, and viruses; airborne transmission, and water transmission; vitamin deficiencies, and food spoilage; some bugs growing in the presence of oxygen, some in the absence of oxygen; mosquitos, and fleas; immune system responses, including both under-reactions and over-reactions – and on and on… In other words, we hadn’t remotely explored the behavioural possibility space of the air and water and food we could see. A special, extra kind of air to one-shot all the problems was not required.

Likewise, today, the idea that we have completely explored the possibility space occupied by baryonic matter, and must instead postulate an entirely new, and totally invisible, form of matter to explain baryonic matter’s behaviour… you can see the absurdity, right? You can see that we are making precisely the same mistake?

Evolved biological systems are complex, and self-organising. Their behaviours feature emergent properties, feedback loops, and interactions across multiple scales. If our universe is itself an evolved system, then it's unsurprising that we're making exactly the same mistake, trying to explain its complex emergent properties using linear causal thinking. Evolved systems resist single-cause explanations. Their behaviors emerge and adjust as the rolling result of weird, unpredictable, interacting networks.

Right now, cosmology suffers from a lethal combination of factors – it has baked ΛCDM into every simulation; it uses it as a background assumption that now underlies, and distorts, every paper in astronomy; and it insists that any alternative solution explain every outstanding observational anomaly in one go, single puzzle-piece style – or if you prefer, miasma-style. This fatal triple-combo has crippled the field’s ability to self-correct.

And again, let me emphasise: whether or not dark matter exists, blowtorch theory clearly explains many phenomena, in the specific area of early structure formation, which that theory cannot.

WHAT’S NEW, PUSSYCAT?

So – for those unfamiliar with the field – what’s novel, and what’s not, in this theory?

Not novel: Supermassive black holes exist at the centers of galaxies, some with accretion disks that emit relativistic jets. That’s now mainstream cosmology. Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs), quasars, blazars, Seyfert Galaxies, Fanaroff-Riley Radio Galaxies – all these powerful, inexplicable phenomena eventually turned out to be supermassive black holes, doing things with jets. (Hey, it’s almost as if these black holes, and their jets, might be ubiquitous and important!)

What’s novel in my theory is the idea that all the supermassive black holes must form first, by direct collapse – before galaxies form, and indeed before there’s any significant number of stars, or (probably) any stars at all. (This emerges directly from the application of Darwinian evolutionary logic to universes. It’s not predicted by any other theory, and if I’m wrong, my theory wobbles badly and a wheel falls off. So the theory is falsifiable. But the evidence from the James Webb Space Telescope so far is very, very encouraging.) Yes, this phase transition occurs incredibly early and activates many powerful, sustained, directional jets very strongly, very quickly. But – no new physics are needed to explain it. In fact, Priya Natarajan, Volker Bromm, Marta Volonteri, and others showed 18 years ago that direct-collapse supermassive black holes are mathematically possible, in brilliant work that was largely ignored at the time. (They, too, will get a late, apologetic Nobel Prize.)

So that's blowtorch theory. But it emerges from – it is both predicted by, and explained by – a larger theory about the universe: three-stage cosmological natural selection. Yes, a theory in desperate need of a shorter, slangier, more vivid, less abstract name. (I find myself calling it the Eggiverse theory – in opposition to the mainstream’s Rockiverse – because it describes our evolved universe rapidly developing upward in complexity over time, like an egg, rather than simply disintegrating slowly, like a rock.)

And three-stage cosmological natural selection – Eggiverse theory – builds on Lee Smolin’s original version of cosmological natural selection.

BACKGROUND: LEE SMOLIN’S ORIGINAL THEORY OF COSMOLOGICAL NATURAL SELECTION (DRAWING ON JOHN WHEELER)

A quick recap for new readers…

Cosmological natural selection assumes that universes reproduce via black holes and big bangs. How? A large mass in a parent universe collapses under its own gravity to form a black hole singularity – an infinitesimal point – that then “bounces”, in a Big Bang, to form a new, expanding, separate bubble of spacetime: a child universe, that exists outside of, and separate from, the parent universe. (The expansion of our own universe since the Big Bang is simply the growth and development to maturity of such a child universe.) If each new universe varies slightly in the fundamental parameters of matter (things like the mass of the electron, or the strength of the strong nuclear force), this will lead to that universe producing either more or fewer black holes, and thus to greater or lesser reproductive success. Over time, this reproduction-with-variation-and-inheritance leads to a Darwinian evolution of universes.

There are analogies with biological evolution: changes in the basic parameters of matter between parent and child universe act like the changes in DNA between biological parents and children: any such variations, or mutations, in the basic parameters of matter will lead to changes in the phenotype of the child universe. (Let’s call it the cosmotype.)

An evolved universe, therefore, constructs itself according to an internal, evolved set of rules baked deep into its matter, just as a baby, or a sprouting acorn, does.

The development of our specific universe, therefore, since its birth in the Big Bang, mirrors the development of an organism; both are complex evolved systems, where (to quote the splendid Viscount Ilya Romanovich Prigogine), the energy that moves through the system organises the system.

But universes have an interesting reproductive advantage over, say, animals.

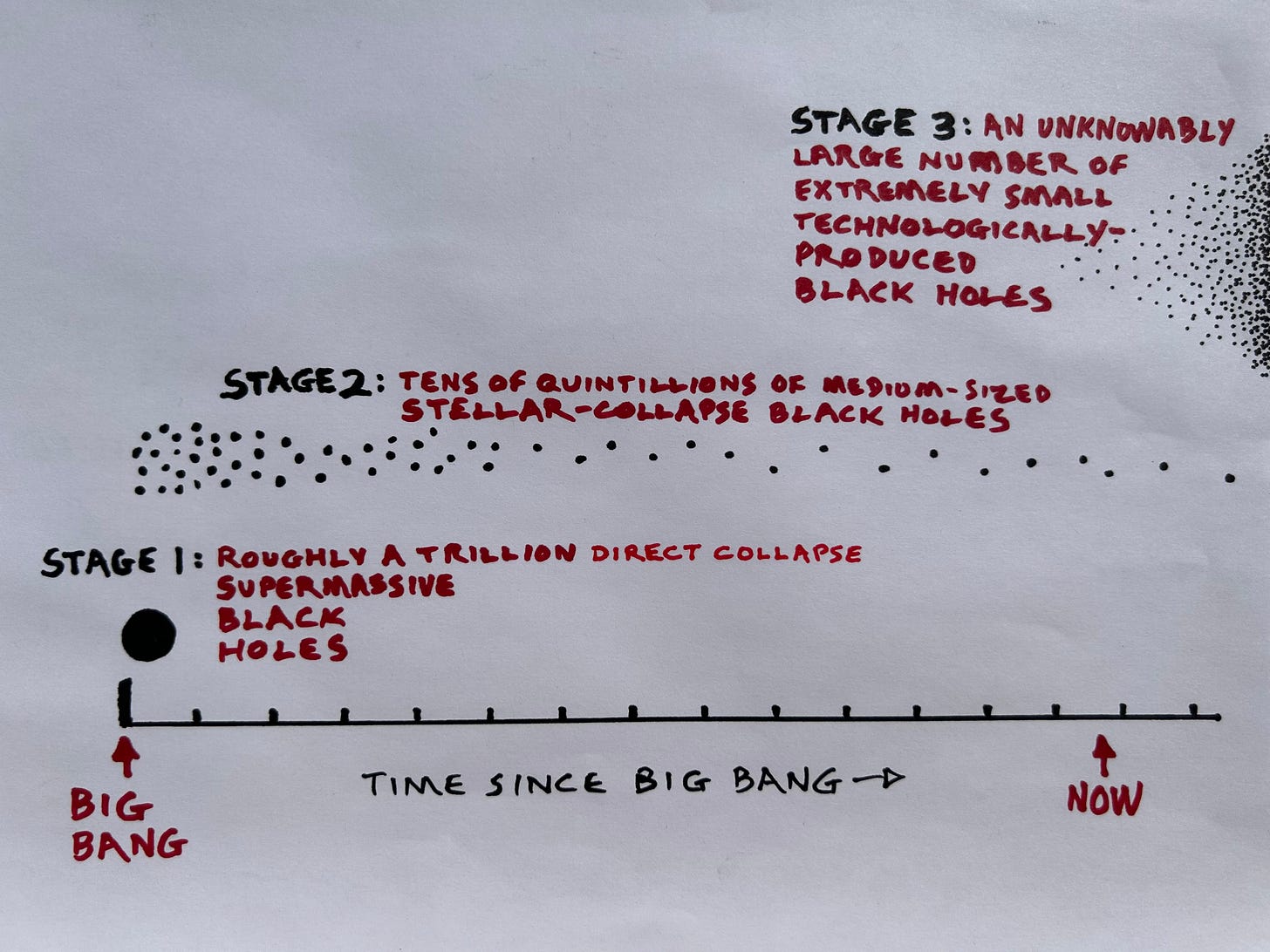

We know that in our own universe, the (positive) mass energy of matter and its (negative) gravitational energy net out to zero. But that means the amount of energy required to build a universe like ours is essentially… well, none. (See Laurence Krauss’s book, A Universe from Nothing; or Stephen Hawking and James Hartle’s 1983 paper, The Wave Function of the Universe, and Hawking’s later book with Leonard Mlodinow, The Grand Design, etc.) Child universes are therefore effectively free to produce. Thus, over time, evolution will favor making more (and smaller) black holes from the same amount of matter. Yes, the black holes will get smaller – but the universes they give birth to, through Big Bangs, will still be full sized. And universes aren’t constrained by a shared environment with limited resources – newborn universes aren’t all competing in a valley with a limited amount of grass. Indeed, each new universe is entirely self-contained and self-sufficient, being both organism and environment – it supplies its own energy for its own development, efficiently and frugally, through stellar fusion, gravitational collapse, et cetera. This means evolution should ultimately favour runaway black hole production. (And that checks out: in the most recent estimate, in 2022, by a team from the International School of Advanced Studies in Trieste, our universe was estimated to have already generated up to a trillion supermassive black holes – and 40 quintillion stellar-collapse black holes.)

A key implication of all these assumptions (which I first pointed out on July 8th 2022 – this theory is undergoing rapid development!), is that direct-collapse supermassive black holes must have been the reproductive mechanism for the earliest, most primitive universes. Primitive universes, like early prokaryotic bacteria, reproduced and nothing else – no complex structures, just straightforward reproduction.

This is a simple black hole/big bang reproductive cycle. Or, if you like, a (contracting) black hole to (expanding) white hole cycle.

Therefore, the mass-energy – the primitive matter – expanding from a Big Bang in an early universe would have quickly collapsed back into a small number of extremely large black holes (supermassive or even ultramassive), without forming stars, galaxies, planets, or even complex elements. Those things all evolved much later along the evolutionary timeline that eventually led to our universe.

Such a basic, ancient reproductive strategy would be conserved by evolution, for the obvious reason that any universes that failed to do this – reproduce – would, in evolutionary terms, die out. (That is, such sterile universes would continue, individually, to exist, growing endlessly older inside their own individual bubble of space-time, but would have no offspring.) Similarly, humans, although far more complex than our jawless fish ancestors, still reproduce as they originally did, by fertilizing an egg – a fundamental reproductive strategy necessarily conserved by evolution.

These conserved, direct collapse, supermassive black holes are, in several important ways, nothing like the, far more common, stellar-mass black holes we also find in our universe (which form when a large star runs out of fuel and collapses under its own gravity). Supermassive black holes are hundreds of thousands, millions, or even billions of times more massive than stellar-mass black holes; I argue that they must have a completely different formation mechanism (direct collapse); and, as we have seen, they perform totally different, and vital, functions in structuring the early universe.

Clearly seeing these differences is vital to understanding our universe.

Yet, for decades, mainstream cosmology (trapped inside Lambda Cold Dark Matter, a paradigm that only allowed for bottom-up structure formation) simply ignored the possibility of direct-collapse supermassive black holes. Instead they argued that the supermassive black holes we kept finding at the centre of galaxies were just a bunch of stellar-mass black holes in a trenchcoat. That the first stars must have been large; formed large stellar-collapse black holes; these quickly merged, and merged again, and again, then happened to drift to the galactic centre thanks to gravity, and then drank in huge amounts of gas. (Yeah, more random, arbitrary, bottom-up structure formation.) Voilà, an accidental, late-to-form, supermassive black hole…

But, as our ever-improving telescopes get us more and more data, from earlier and earlier, it gets harder and harder to make the maths add up. We are now able to observe supermassive black holes shockingly close to the Big Bang, when the universe was just 3% of its current age. There simply isn’t enough time for them to have formed from lots of smaller stellar-mass black hole mergers.

And so the supermassive black holes in our universe today presumably formed the same way as in our distant ancestral universes: by direct collapse of a massive, smooth gas cloud – without needing to build stars first – very soon after the Big Bang.

But why isn't our universe still fine-tuned by evolution to turn all its gas into supermassive black holes immediately after the Big Bang? Because, over time, it evolved a new, sophisticated, multi-stage reproductive cycle that takes billions of years. There are many analogies for this in biology; we know this is what evolution does. Primitive bacteria, for example, reproduce a single all-purpose cell in 20 minutes; complex beings like humans reproduce trillions of specialised cells, in a more complex process that takes decades. Both are successful, but in their own evolutionary contexts.

So here, the unit of selection isn’t a single galaxy; it’s the entire universe – a trillion galaxies contained within a single, expanding membrane of spacetime, like the trillions of cells contained by a human’s skin. And what matters is reproduction (black hole production) over its full lifespan.

THAT THIRTEEN-SYLLABLE THEORY AGAIN

TIMELINE: To fully understand this, you’ll need the three-stage model of cosmological natural selection. (Good old Eggiverse theory.)

1990s: Smolin’s original theory was a limited, single-stage model because, back then, it was still assumed all black holes, whatever their size, were made out of stellar-collapse black holes.

2000s: Vidal, Smart, Price and Kane expanded this to a two-stage model, adding technologically-produced small black holes. (This explained why evolved universes might generate life – a brilliant conceptual breakthrough, again overlooked at the time.)

2020s: I develop the three-stage model, incorporating direct-collapse supermassive black holes – the model which led to blowtorch theory, and which generates the predictions we’re seeing here.

THE THREE-STAGE MODEL OF COSMOLOGICAL NATURAL SELECTION

STAGE 1: DIRECT COLLAPSE SUPERMASSIVE BLACK HOLES

Right at the start, in a phase transition shortly after the big bang, a relatively small number of supermassive black holes quickly form by direct collapse. (Very roughly a trillion, of assorted sizes.)

That is the original reproductive mechanism for universes, conserved by evolution.

STAGE 2: STELLAR-MASS BLACK HOLES

However, these supermassive black holes only use up a fraction of the gas in the universe. They then shape and direct much of the remaining gas so as to form galaxies around themselves – one galaxy (containing hundreds of millions to hundreds of billions of stars) per supermassive black hole. These galaxies thus eventually generate many more stellar-mass black holes than the initial set of supermassive ones. (Thus, overall, far more black holes – offspring – per unit mass.) This more complex, highly efficient method of reproduction evolved later in the history of universes and has likewise been conserved, because it leads to…

STAGE 3: TECHNOLOGICALLY PRODUCED SMALL BLACK HOLES

In a more sophisticated stage 3 universe, after two or three rounds of star formation, galaxies have built out (through fusion) and distributed (through supernova explosions) the periodic table of all the elements.

This allows planets and moons to form around third-round stars like our own sun. (And stanets and ploons to form in open space… but that’s another story.) Sunshine and/or gravitational energy then drive the development of the complex organic chemistry of biology: Biology is the first half of the periodic table coming to life. Eventually, that life, rapidly self-complexifying on countless billions of habitable worlds per galaxy, attains intelligence and technological ability. (It has swiftly done so on our own perfectly average planet – so we know this happens.) Technology is the second half of the periodic table coming to life. At which point, those intelligent, technology-wielding lifeforms begin creating vast quantities of extremely small black holes for energy production.

Biology is the first half of the periodic table coming to life.

Technology is the second half of the periodic table coming to life.

-Me (trying to boil this whole theory down into t-shirt memes)

Q: Why black holes?

A: Because you can just chuck any matter at all into them, and they can convert up to 42% of its mass into energy, making them the most efficient energy source in our universe. (And, as my friend Yogi has pointed out, the most sustainable – you could keep a civilization and its ecosystem alive by this method long after all the uranium’s been used up; indeed, long after all the stars have gone out.) By comparison, nuclear fission converts only 0.1% of mass into energy, and fusion 0.7%. So, any intelligent species optimizing for energy efficiency (and sustainability) will eventually converge on small black hole production. (Optimal size is roughly Mount-Everest-mass.) As the production of countless small black holes by technology-wielding lifeforms means huge reproductive success for that universe, such life will be intensely selected for, and strongly conserved. Most universes along our evolutionary branch should, by now, generate such lifeforms. Again, that’s because such Stage 3 universes will produce, over their lifetime, far more black holes per unit mass than will either Stage 1 or Stage 2 universes.

HOW THE BLOWTORCH THEORY MAKES EVOLUTIONARY SENSE

This third reproductive mechanism is far more complex than the first two (it’s more highly evolved!), and it requires the individual universe to have a much longer active lifespan. In particular, it needs multiple rounds of star formation to take place within the individual universe, over billions of years, to build out and distribute the entire periodic table – and thus planets, moons, life, and eventually, technology.

If our universe were to use up all its gas early, just to make a few more first-round, low-metallicity stars and simple stellar-mass black holes, we’d never reach this third and most reproductively successful stage.

So that pure hydrogen gas left over from the Big Bang has to be carefully rationed and delivered to spiral galaxies over billions of years. But it also needs to be enriched – because you can’t easily make stars out of pure hydrogen and helium alone. You need heavier elements – rather annoyingly dubbed “metals” by astronomers (even when, like nitrogen and oxygen, they’re not metals). In spiral galaxies, first-round stars blow up and distribute these “metals” back into the pure hydrogen that’s streaming in from the filaments. That enriched gas then gathers in the specialised regions in the arms of spiral galaxies we call “stellar nurseries”, ready for the next round of star formation. (Stellar nurseries… Interesting name, huh? I suspect that, at a deep subconscious level, many astronomers already know this is an efficient, evolved, quasi-biological process.)

So spiral galaxies can store, channel, enrich, and drip-feed this primal hydrogen gas back to their stellar nurseries, where carbon and oxygen from past supernovae help refrigerate it (and enrich it), allowing it to collapse to form next-round stars. This absurdly intricate process is driven by the delicately balanced interplay of gravitational and electromagnetic forces. It’s clearly a fine-tuned system, evolved for optimal star-planet-moon-life-technology creation. Why “clearly fine-tuned?” Because such a result is unbelievably unlikely – yet, look around you, that's what it does. (Just as Fred Hoyle predicted that the fusion process in stars was fine-tuned to produce and distribute the elements – because look around you, that's what it does.)

EXCEPTIONS PROVE RULES: ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES

But let’s take a quick look at elliptical galaxies. These are 10-15% of all galaxies, with roughly spherical shapes, intense but early star formation – and long-term struggles to replenish their gas. Lacking the intricate gas management system of spiral galaxies, ellipticals burn out quickly, typically failing to form the large amounts of the full suite of elements essential for planets, life, and tech. Ellipticals make SOME elements, and distribute them, obviously, as their larger stars run out of fuel and blow up as supernovae – but they don’t go through multiple rounds of star formation, over billions of years, methodically building out ever-greater amounts of heavier elements by recycling and refining them, in the way spirals do. And yes, some ellipticals are still active, as other galaxies crash into them, bringing fresh gas – but most are red and dead.

So what’s the story with ellipticals? Well, let me speculate: if our universe is the result of the evolutionary process I outlined above, then they’re probably the vestiges of an earlier cosmic age, like our own vestigial tailbone, or the fur in our armpits. All galaxies would've been ellipticals (or similar) at Stage Two, when only rapid star-making mattered. (Ellipticals are brilliant at extremely rapid star-making!)

EVOLUTIONARY TRACES: TAU, MUON, ELECTRON

Evolution moves on, but it drags elements of its evolutionary past around with it, it can’t simply make a clean break. Similarly, the three-stage model of cosmological natural selection explains why three kinds of electron can be produced in our universe – but only one usually is, under normal conditions. Extremely heavy tau electrons (roughly 3,500 times the mass of a normal electron), and heavy muons (roughly 200 times heavier), are presumably fossil particles from stage one and stage two respectively. (Interestingly, the Nobel-Prize-winning Japanese physicist Yoichiro Nambu intuited this as far back as 1985, in his wonderful essay Directions of Particle Physics, but had no theory to explain it.) Just to make it clear, this is much more speculative than the theory it’s based on. But it’s a speculation I find intriguing, and you might find interesting.

Evolutionary Stage 1: An extremely heavy electron (the tau) made evolutionary sense when all you had to do was maximise immediate direct-collapse black holes. Mass was king! The positive and negative particles probably had roughly the same mass back then, but it didn’t matter; they weren’t building anything complicated.

Evolutionary Stage 2: A less heavy (but still pretty heavy!) electron (the muon) would have been ideal if you still needed to make some supermassive black holes, but were now optimising for, more numerous, stellar-collapse black holes. You only needed to be able to make a couple of primitive elements, through primitive fusion.

And Evolutionary Stage 3: Our modern, lightweight electron was the evolutionary breakthrough that allowed the assembly, by fusion, of many more (more complex) elements, and thus complex chemistry, life, and technology – optimising for FAR more numerous technologically-produced black holes…

All universes, like all biological DNA-based organisms, are forever a little messy; forever transitional between what they once were, and what they might yet be.

For example, the carbon, nitrogen and oxygen that originally evolved to drive efficient stellar fusion in Stage 2 universes, through the CNO cycle, were later exapted (adapted for a new purpose by evolution) as the basis for biological life in Stage 3 universes.

Likewise, just look through a telescope, and you can see handfuls of the red-and-dead elliptical galaxies that must have dominated those Stage 2 universes.

Fire up a particle accelerator, and you can bring to life ghost particles like the tau and muon, still implicit in our quantum fields, even though they have long been banished from our everyday world by the ongoing evolution of the other parameters of matter.

Those traces of our evolutionary past, embedded in our present, mean that we can trace the evolutionary history of universes, even though we only have a single specimen to examine – the universe we are embedded inside, that we are part of. The universe that recently generated us, as part of its developmental process. The universe that is coming to know itself through us; act on itself through us. The universe in which we are currently helping sand to think.

Okay. As Tyler Cowen gently pointed out to me, when I showed him an earlier draft of this, a good theory makes predictions.

So here are some.

PREDICTIONS

Supermassive black holes form first, in a phase change that precedes stars and galaxies

We will see a wave of direct collapse supermassive black hole formation (numbering a trillion or so), well inside the first 100 million years after the Big Bang. (And almost certainly inside the first fifty million.) This wave precedes star and galaxy formation.

Those early supermassive black holes will be found to spin at close to the Kerr limit

As all the angular momentum in the entire vast cloud is conserved, the spin rate of these direct collapse supermassive black holes will approach the Kerr black hole spin limit (very close to the speed of light). Later mergers, plus infills of randomly oriented gas and stars, etc, will often lower that spin rate, making them less efficient: but they are born at close to maximum efficiency.

Those extremely fast-spinning, efficient supermassive black holes then generate stars and galaxies

It is the supermassive black holes which generate the galaxies around themselves, by attracting, shocking, and enriching the surrounding gas to precipitate waves of star formation.

Meanwhile, they generate the cosmic web

A trillion quasars switch on immediately, blasting out powerful, sustained relativistic jets, which create both the low-pressure, lightly-magnetized cavities and the high-pressure, highly-magnetized pipes that merge and expand to form the voids and filaments of the cosmic web.

But it’s simply hard to see anything at all from the first fifty million years after the Big Bang, let alone the detailed picture I’ve just described – even with the James Webb Space Telescope. So here are some specifics we can look for, using a variety of methods, some available right now:

Gravitational waves: The Popcorn Signature

Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime, caused by large masses moving asymmetrically. As our gravitational wave detectors (like the wonderful Pulsar Timing Arrays I wrote about here) grow more sensitive, and able to locate events further and further back in space and time, we will find the gravitational-wave traces of that original brief era of direct collapse supermassive black hole formation coming from all over the sky, in lots of faint, overlapping, low-frequency gravitational waves. It’s true that any initial perfectly symmetrical collapses wouldn’t generate waves (no rough edges = no splash = no ripple), but as the smoothness breaks down, the later, slightly less symmetrical collapses should, as should any early mergers.